United States General Accounting Office

GAO

Report to the Subcommittee on

Workforce Protections, Committee on

Education and the Workforce, U.S.

House of Representatives

September 1999

FAIR LABOR

STANDARDS ACT

White-Collar

Exemptions in the

Modern Work Place

GAO/HEHS-99-164

GAO

United States

General Accounting Office

Washington, D.C. 20548

Health, Education, and

Human Services Division

B-283016

September 30, 1999

The Honorable Cass Ballenger

Chairman

The Honorable Major R. Owens

Ranking Minority Member

Subcommittee on Workforce Protections

Committee on Education and the Workforce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Bill Goodling

Chairman

The Honorable William Clay

Ranking Minority Member

Committee on Education and the Workforce

House of Representatives

After more than 60 years, the Fair Labor Standards Act (

FLSA) remains the

primary federal statute setting the minimum wage and hour standards

applicable to most American workers. Since its enactment in 1938, the

industrial profile of the American economy has shifted dramatically,

changing from predominantly manufacturing to increasingly

service-oriented. Critics of the

FLSA claim that this shift, as well as the

increased use of sophisticated technology, have left the

FLSA and its

regulations outdated and in need of revision.

One area of concern involves the so-called “white-collar” exemptions of

the

FLSA. The Act limits the normal work-week to 40 hours, requiring most

employers to pay hourly overtime wages to employees who work longer

than 40 hours. However, under section 13(a)(1) of the Act, employees

working in a “bona fide executive, administrative, or professional

capacity” are exempted from the wage and hour standards. These

white-collar employees need not be paid overtime premium pay for a

work-week longer than 40 hours.

Employers from both the private sector and state and local governments

have focused their criticisms on Department of Labor (

DOL) regulations

that define the “exempt” white-collar employees. Under the

FLSA, DOL is

responsible for setting the criteria for these exemptions, and historically it

has formulated specific regulatory tests based on the accumulated

experience of employers, employees, and its own field staff with

work-place issues. Currently, employees must meet each of three tests to

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 1

B-283016

be classified as exempt white-collar workers: (1) the employee must be

paid a salary, not an hourly wage (the salary-basis test); (2) the amount of

the employee’s salary must indicate managerial or professional status (the

salary-level tests); and (3) the employee’s job duties and responsibilities

must involve managerial or professional skills (the duties tests).

In response to your request for information on employer compliance with

the white-collar exemptions under the

FLSA, this report focuses on five

questions: (1) How many employees are covered by the white-collar

exemptions and how have the demographic characteristics of these

employees changed in recent years? (2) How have the statutory and

regulatory requirements changed since the enactment of the

FLSA?

(3) What are the major concerns of employers regarding the white-collar

exemptions? (4) What are the major concerns of employees regarding the

white-collar exemptions? (5) What are possible solutions to the issues of

concern raised by employers and employees? We performed our work in

accordance with generally accepted governmental auditing standards from

November 1998 through June 1999. Our scope and methodology are

presented in appendix I.

Results in Brief

In 1998, between 20 and 27 percent of the full-time U. S. workforce—or 19

to 26 million workers—were executive, administrative, or professional

employees covered by white-collar exemptions of the

FLSA.

1

In recent years

the percentage of employees covered by these exemptions has been

increasing. The number of employees working in certain service industries

2

nearly doubled between 1983 and 1998, and there is a higher percentage of

white-collar employees in the service sector than in other sectors of the

economy, such as manufacturing. Overall, the workforce covered by the

exemptions also became increasingly female—the proportion of women

increased from 33 percent in 1983 to 42 percent in 1998. In addition, in

1998, workers subject to the white-collar exemptions were more than

twice as likely as nonexempt workers to work overtime—44 percent of

exempt employees worked more than 40 hours in a work-week, and about

one-third of those worked more than 50 hours in a work-week.

1

Our estimate includes only those employees who would most likely be properly classified as exempt

workers under the DOL regulations. It may not include all employees who are classified as exempt

workers by their employers.

2

These industries included four types of service occupations from the Current Population Survey

(CPS) industry codes: business and repair, personal, entertainment and recreation, and professional

and related services. For definitions of other industries discussed in this report, see app. I.

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 2

B-283016

In the 16 years following the 1938 enactment of the FLSA, DOL established

the key regulatory tests defining whether an employee can be classified as

an exempt white-collar worker. These tests included the salary-basis

test—the requirement that exempt white-collar workers be paid a salary,

not an hourly wage—as well as the various salary-level and duties tests.

Since 1954, major statutory and regulatory changes to the white-collar

exemptions have been few, and primarily limited to increases in the

salary-test levels and to changes to coverage of specific types of

employees. In recent years, for example, the salary-basis test has been

adjusted for state and local government employees, and higher-wage

computer programmers were included in the exemption.

In general, employers we contacted were concerned that the regulatory

tests were too complicated and outdated. Specifically, their concerns

included the following:

• Employers worried about potential liability for violations of the

salary-basis test. While

DOL viewed the test as being a highly accurate

indicator of managerial and professional status, in recent years it has been

the focus of legal suits brought collectively by groups of managerial and

professional employees against their employers. Our review of federal

cases and discussions with employers showed continuing uncertainties

and difficulties with the test.

• Employers also believed that the regulations limiting the exemptions to

white-collar nonproduction employees did not take into account the effect

of modern technology on employment. For example, they pointed to

highly skilled and well-paid technicians who did not qualify as exempt

professionals, but who performed essentially the same job as exempt

engineers with the required academic degrees.

• Finally, employers complained that the parts of regulatory duties tests that

call for independent judgment and discretion on the part of those

classified as administrators and professionals led to confusing and

inconsistent results in classifications of similarly situated employees. Our

discussions with

DOL investigators and review of compliance cases

indicated that this part of the duties test involved difficult and sometimes

subjective determinations, and that it was a source of contention in

DOL

audits.

Employee representatives, on the other hand, were most concerned about

preserving work-hour limitations for employees, and believed that the

regulatory tests, as applied today, were not sufficient to adequately restrict

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 3

B-283016

the use of the exemptions by employers. Specifically, they cited the

following concerns:

• Employee representatives believed that inflation has severely eroded the

salary-level limitations originally envisioned by the

DOL regulations. The

regulations create three levels of regulatory duties tests, depending on

employees’ salaries. Under the regulations, the lower the employee’s

salary, the greater the limitations on the use of the exemptions. However,

the regulations do not provide for automatic or periodic adjustments of

the salary levels, and the levels have not been changed since 1975. To fully

account for inflation between 1975 and 1988, the salary levels would have

to be increased about threefold. As a result of the increase in salaries over

that period, almost all full-time employees in 1998 were covered by the

least-restrictive regulatory duties test—leaving more people than ever who

potentially fall under the white-collar exemptions.

• The representatives contended that the duties test for executive

employees has been oversimplified, leading to inadequate protection of

low-income supervisory employees. Our review of federal case law and

DOL compliance cases indicated that it is, in fact, difficult to challenge

exempt classifications if employees supervise two or more full-time

employees and spend some time—even if minimal—on management tasks.

Although various proposals have been advanced to address the concerns

raised in this report, the conflicting interests of employers and employees

have made resolution difficult. Some proposals would, for example,

eliminate the salary-basis test or raise the salary-test levels. However, for

every proposal—even those with consensus, such as increasing the

salary-test levels—there are competing interests to be considered. To

resolve these issues, the desire of employers for clear and unambiguous

regulatory standards must be balanced with that of employees for fair and

equitable treatment in the work place. Although

DOL established the

regulatory tests by balancing these competing interests, these same

interests have made

DOL reluctant to alter the current regulatory structure.

In the last 45 years,

DOL has adjusted the FLSA regulations only in a

piecemeal fashion to meet the needs of particular types of employers and

employees. Given the economic and work place changes over this period,

a more comprehensive look at these regulations is necessary to determine

whether a consensus could be achieved on how to amend the regulations

to better suit the modern work place. This report recommends that the

Secretary of Labor comprehensively review current regulations and

restructure white-collar exemptions to better accommodate today’s work

place and to anticipate future work place trends.

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 4

B-283016

Background

The FLSA sets the minimum wage most employers must pay their

employees and the maximum hours—40 per week—most employees can

work without receiving extra, overtime premium pay (at time-and-one-half

the regular rate). In addition, the

FLSA specifies which workers are exempt

from these requirements. Although numerous categories of workers are

exempt from these requirements,

3

the largest group of exempt workers

includes employees classified as executives, administrators, or

professionals under section 13(a)(1) of the Act. These are sometimes

called the white-collar exemptions, although not all white-collar

employees are exempt.

The

FLSA was enacted to address problems associated with substandard

working conditions by establishing a floor on wages and a ceiling on

hours, beyond which the employer was required to pay extra wages. The

purpose of the overtime provision was to shorten the work-week to a

more reasonable 40 hours. This was expected to result in less employee

fatigue, fewer accidents, higher productivity and efficiency, and more

employee time for education and family duties. By requiring overtime

premium pay, it was expected that employers would hire more workers to

avoid the extra wage costs, and that workers would be assured additional

pay to compensate them for the burden of a work-week in excess of 40

hours. The Minimum Wage Study Commission of 1981

4

justified the

exemption of executives, administrators, and professionals from the

protections of the

FLSA in part because these employees were associated

with higher base pay, higher promotion potential, and greater job security,

making them different from other employees. Moreover, the nature of their

jobs—managerial and professional—precluded the potential for the job

expansion desired in other types of employment (that is, hiring more

workers to perform the additional hours of work).

For employers and employees, the practical consequences of the exempt

worker classification can be very important. An exempt employee may be

required to work as many hours as it takes to complete a task. Although

this may be more than 40 hours per week, the employee will not be

entitled to overtime premium pay for the hours exceeding 40. Thus, an

exempt financial manager may be required to work 60 hours a week and

be paid a set weekly salary. On the other hand, a nonexempt bookkeeper

3

Currently, section 13(a) lists 10 other categories of workers (in addition to managers and

professionals) as exempt from both the minimum wage and maximum hours provisions of the FLSA.

These include diverse groups of employees, such as babysitters and those working at recreational

establishments.

4

The legislative history for the FLSA contains no explanation for the exemption.

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 5

B-283016

may also be required to work 60 hours per week, but must be paid at a

premium hourly wage for 20 hours (the number exceeding 40 per week) in

addition to a set weekly salary.

5

Ever since the FLSA was enacted, the interests of employers in expanding

the white-collar exemptions as broadly as possible have competed with

those of employees in limiting use of the exemptions. In 1940, for example,

DOL reported that groups representing employers argued for broader use of

the exemptions to allow management training, to increase flexibility in

work-hour scheduling, and to ensure a stable weekly pay for employees.

At the same time, employee representatives argued against broader use of

the exemptions, trying to reduce the potential for abuse and exploitation

of workers.

Balancing the competing interests of employers and employees,

DOL

established specific regulatory tests that must be met before an employee

can be classified as an exempt white-collar

6

worker. In general, there are

three major parts to these tests:

• First, the employee must be paid on a salary basis, not at an hourly rate.

This means that the employee must be paid a guaranteed amount each pay

period, independent of the number of hours that the employee has actually

worked and the quality and quantity of work performed.

• Second, the employee must be paid at least a specified base salary level

that indicates managerial or professional status.

DOL regulations include

different salary levels. One is a base level for each type of exempt

white-collar worker—executive, administrative, or professional—below

which workers are assumed to be nonexempt and covered by the

FLSA

minimum wage and overtime requirements. The other is a higher salary

level, above which employees will likely be exempt if their primary duties

are managerial or professional.

• Third, the employee must have duties and responsibilities associated with

managerial or professional work. Generally, such duties must include

appropriate independent judgment and discretion. However, depending

upon the employee’s salary level—whether it is above or below the highest

salary level—

DOL regulations call for either closer scrutiny (with a long,

detailed test) or not as much scrutiny (with a short, limited test) of the

nature of the employee’s duties.

5

Salaried workers may be either exempt or nonexempt; being paid a salary is not determinative of

exempt status.

6

DOL does not refer to a white-collar exemption; the exemption is referred to routinely as covering

executive, administrative, and professional employees.

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 6

B-283016

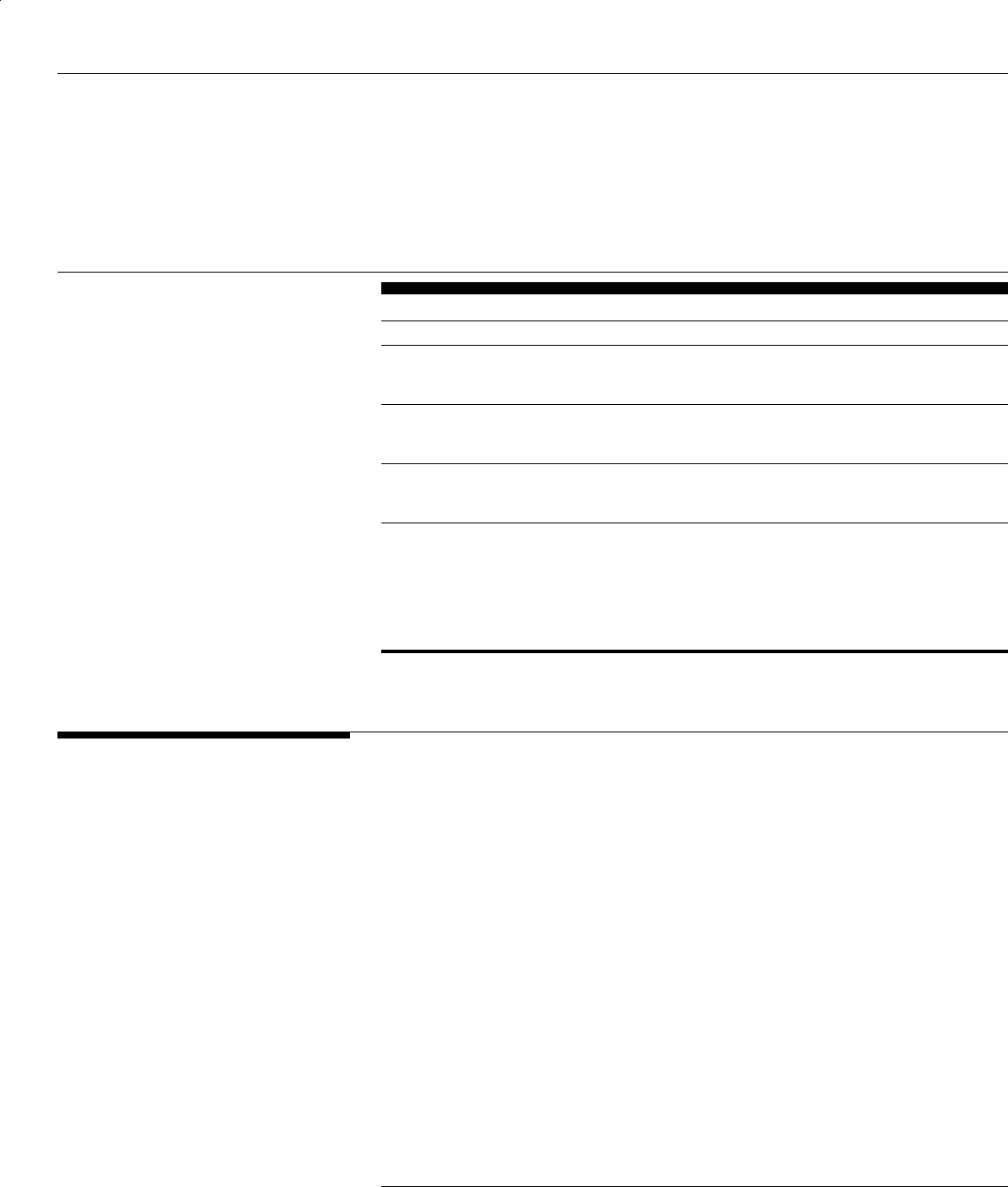

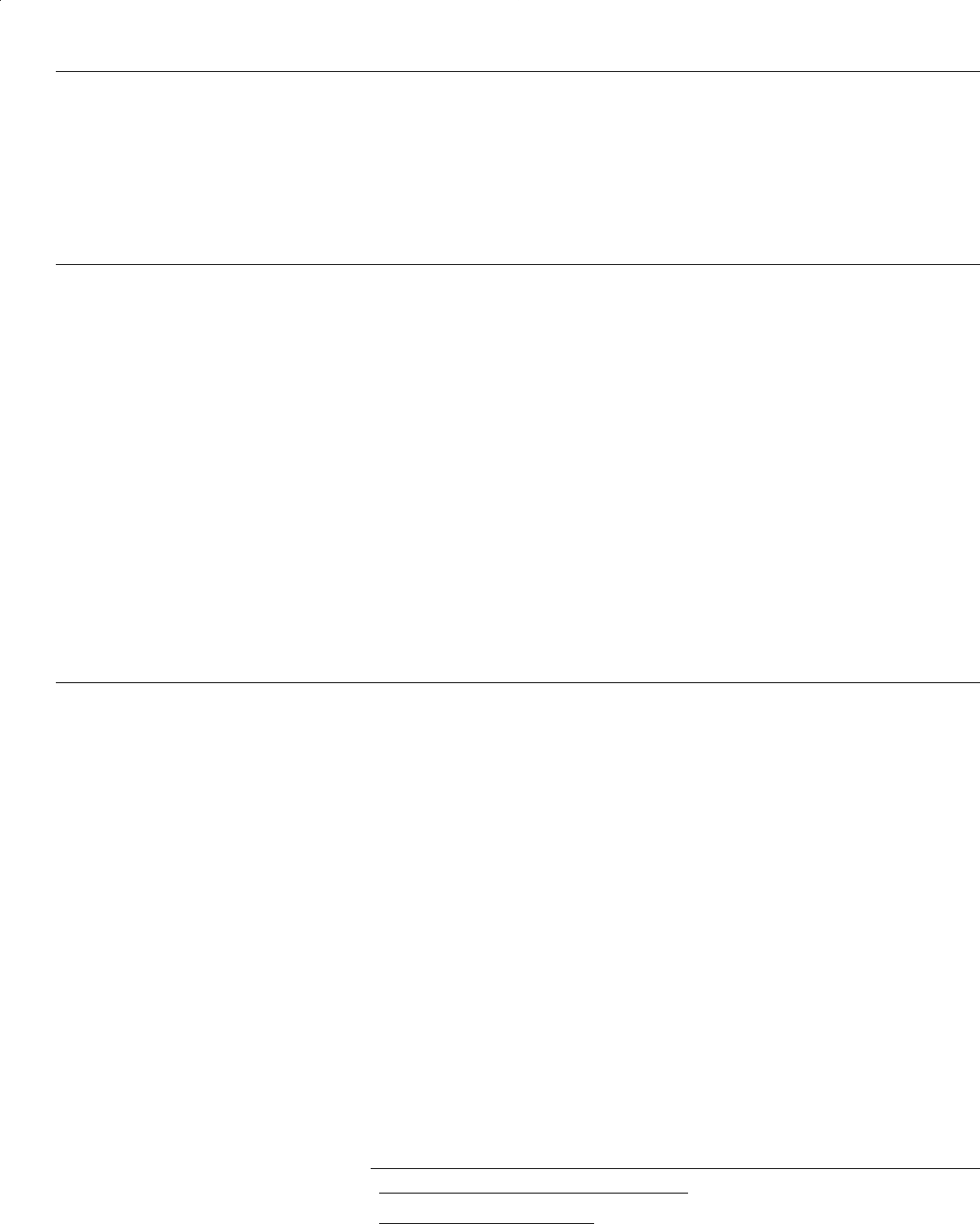

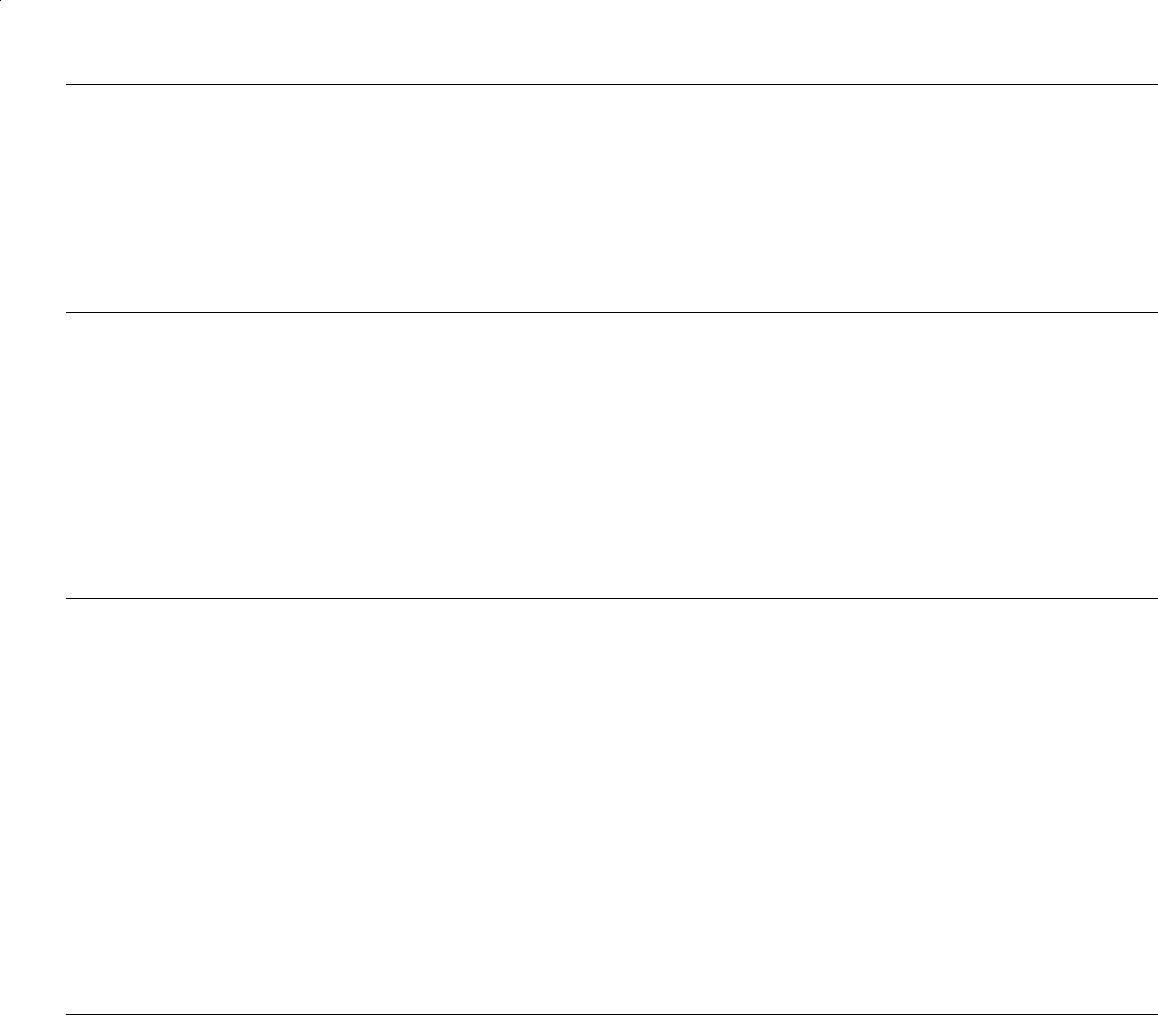

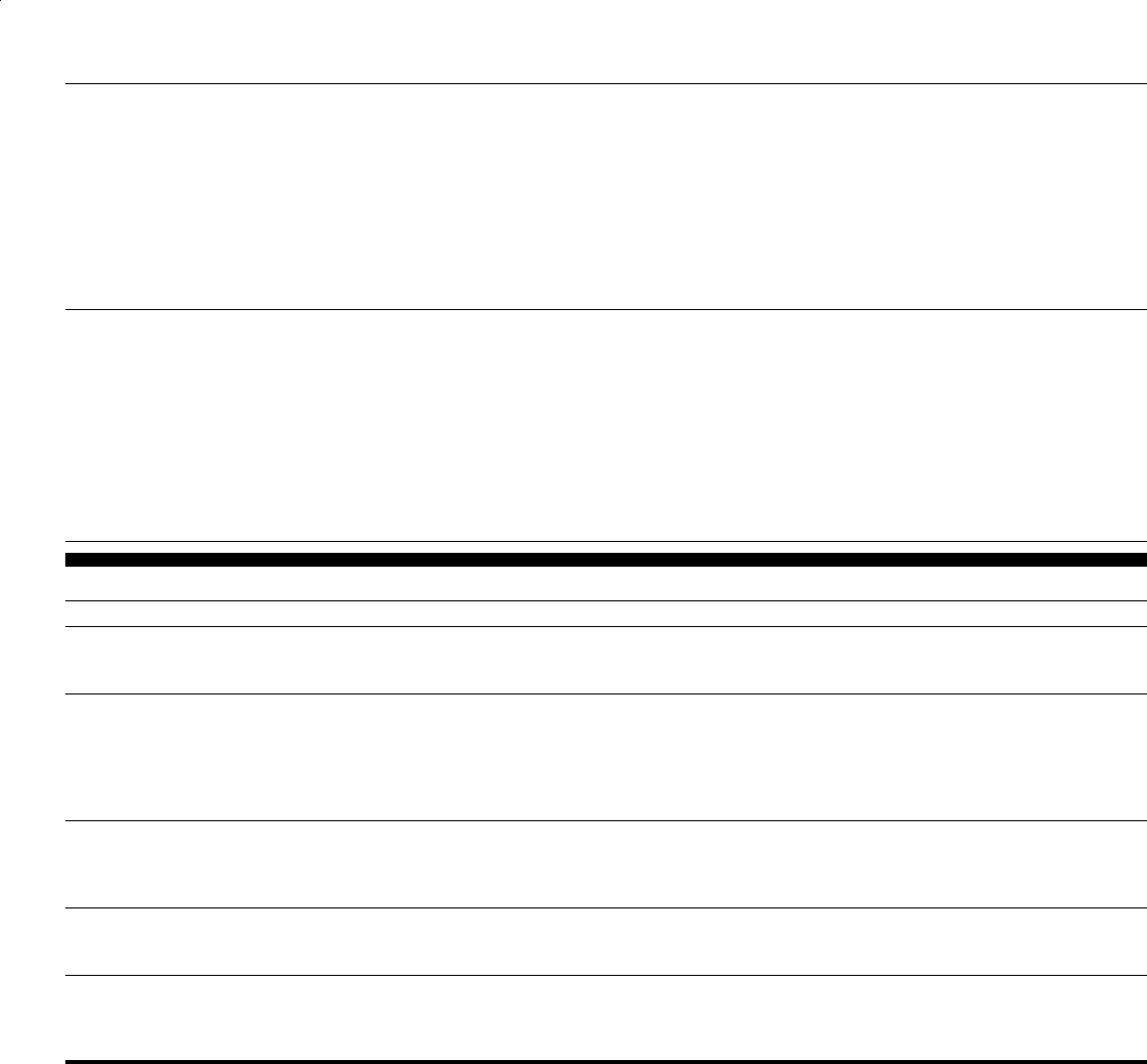

The regulatory tests vary among the three categories of

employees—executive, administrative, and professional. Table 1

summarizes the major tests required for each type of exemption. For each

category of employee, we identify the salary levels included in the

regulations and the associated duties test. We refer to the lower salary as

the base salary, and the applicable duties test as the long test. The higher

salary level is referred to as the upset test, and the applicable duties test as

the short test.

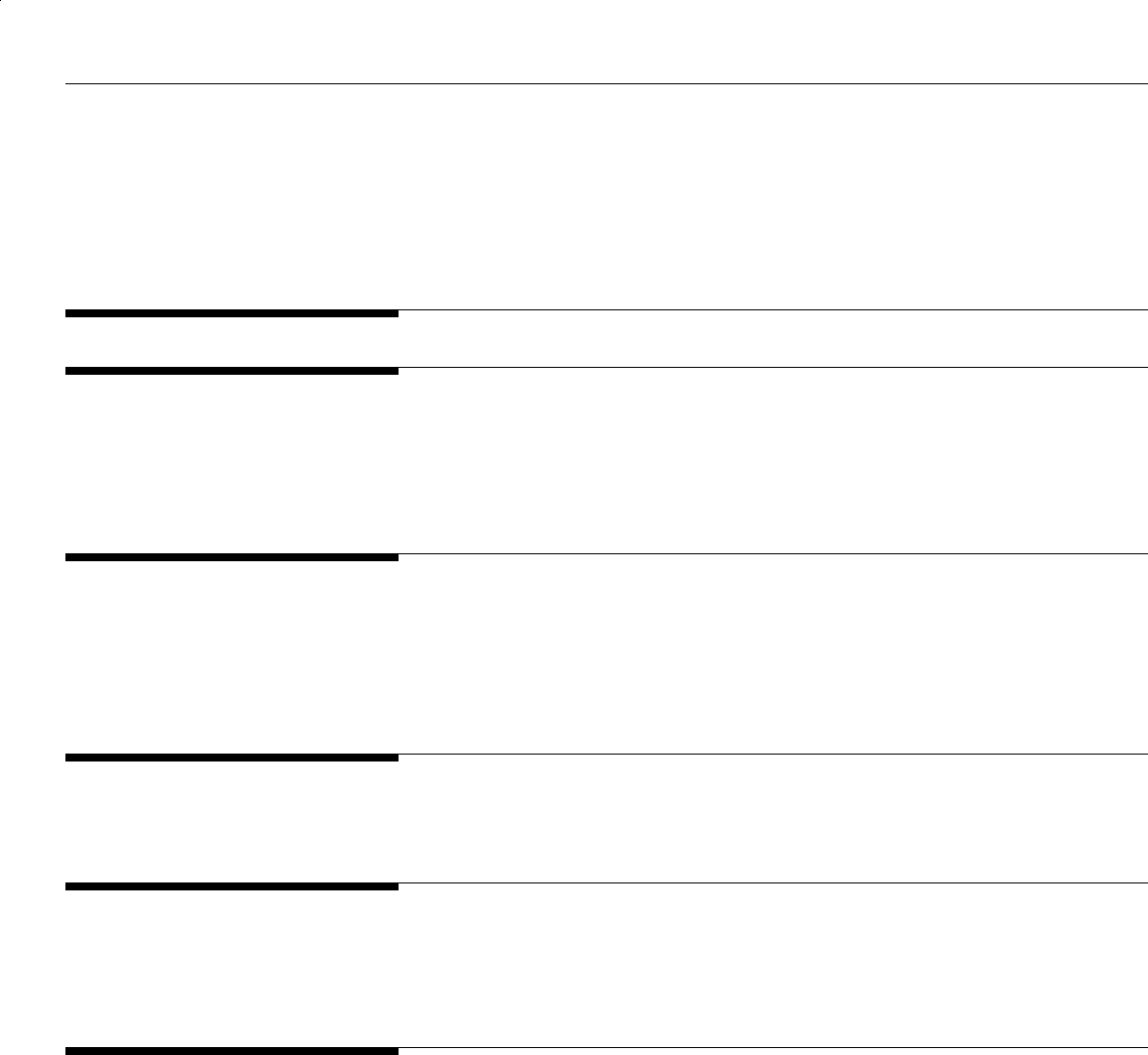

Table 1: Summary of Current Regulatory Tests for Executive, Administrative, and Professional FLSA Exemptions

Employee type Paid a salary

Base salary

(triggers long

duties test) Long duties test

Upset salary

(triggers short

duties test) Short duties test

Executive Yes $155 per week Various indicators,

including a primary

duties test and a

requirement that no

more than 20 percent of

work (or 40 percent if in

retail or service) involve

nonmanagerial work

$250 per week (1) Must supervise two or

more employees, and (2)

primary duty must be

management

Administrative Yes; also may

be paid on a

fee basis

$155 per week Primary duties test

including the

percentage limitations

on nonexempt work,

plus other indicators of

administrative

responsibilities

$250 per week (1) Primary duty must involve

office or nonmanual (or staff)

work directly related to

management, and (2) work

must require discretion and

independent judgment

Professional Yes; also may

be paid on a

fee basis

$170 per week Primary duties test

including the

percentage limitations

on nonexempt work,

plus other indicators of

professional

responsibilities

$250 per week Either (1) must have requisite

academic degree and job

must require consistent

exercise of discretion and

independent judgment, or (2)

must involve original and

creative work requiring

invention, imagination, or

talent in recognized field

Source: GAO analysis of DOL regulations.

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 7

B-283016

Number of

White-Collar

Exemptions Increases

With Growth of

Service Sector

We estimate that between 19 and 26 million full-time wage and salary

workers

7

were covered by the white-collar exemptions in 1998.

8,9

This

amounts to 20 to 27 percent of the full-time labor force. Based on the high

estimate of 26 million, our estimate represents an increase of 9 million

workers over our 1983 estimate of 17 million exempt full-time wage and

salary workers (see table 2). For a detailed description of the methods

used to obtain these estimates, see appendix I.

Table 2: Estimates of Full-Time White-Collar Workers Exempt in 1983 and 1998

High estimate Low estimate

Covered by white-collar exemptions

Year

Total full-time wage

and salary workers

(millions)

a

Number of

employees

(millions)

Percentage of

full-time wage and

salary workers

Number of

employees

(millions)

Percentage of

full-time wage and

salary workers

1983 71 17 24% 12 17%

1998 96 26 27% 19 20%

Notes: Includes employees exempt under sec. 13(a)(1) of the FLSA. 29 C.F.R. 541 defines those

employees classified as executive, administrative, professional, or outside sales workers. Outside

sales workers are not included in this analysis. Please see app. I for a discussion of these

estimates.

a

Wage and salary employment numbers are from the CPS Outgoing Rotations Data analysis and

match the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)-published Employment and Earnings annual

averages.

Source: CPS Outgoing Rotations Data for 1983 and 1998.

Much of the growth in exempt workers can be attributed to the growth in

the service sector of the economy. In 1998, the service industries

employed 24 million full-time workers—nearly doubling from 13 million

workers in 1983. All sectors of the labor market saw some growth in the

number of workers between 1983 and 1998;

10

however, no other sector has

7

Full-time wage and salary workers exclude self-employed workers and workers under age 16.

8

For each of 257 job titles, DOL provided us with a range estimate—for example, 10-50 percent—of the

employees in that job category who would probably be exempt. We arrived at our low estimate

(19 million) by using the lower ends of DOL’s individual job category range estimates, and at the high

estimate (26 million) by using the upper ends of those individual estimates.

9

Our work is not an attempt to count the actual number of people classified as exempt by American

employers, but rather to estimate how many full-time workers are covered by the white-collar

exemptions.

10

The number of full-time wage and salary workers grew between 1983 and 1998 as follows: services,

13 to 24 million; retail trade, 8 to 13 million; manufacturing, 18 to 19 million; finance, insurance, and

real estate, 5 to 7 million; other, 14 to 18 million; and public sector, 13 to 16 million.

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 8

B-283016

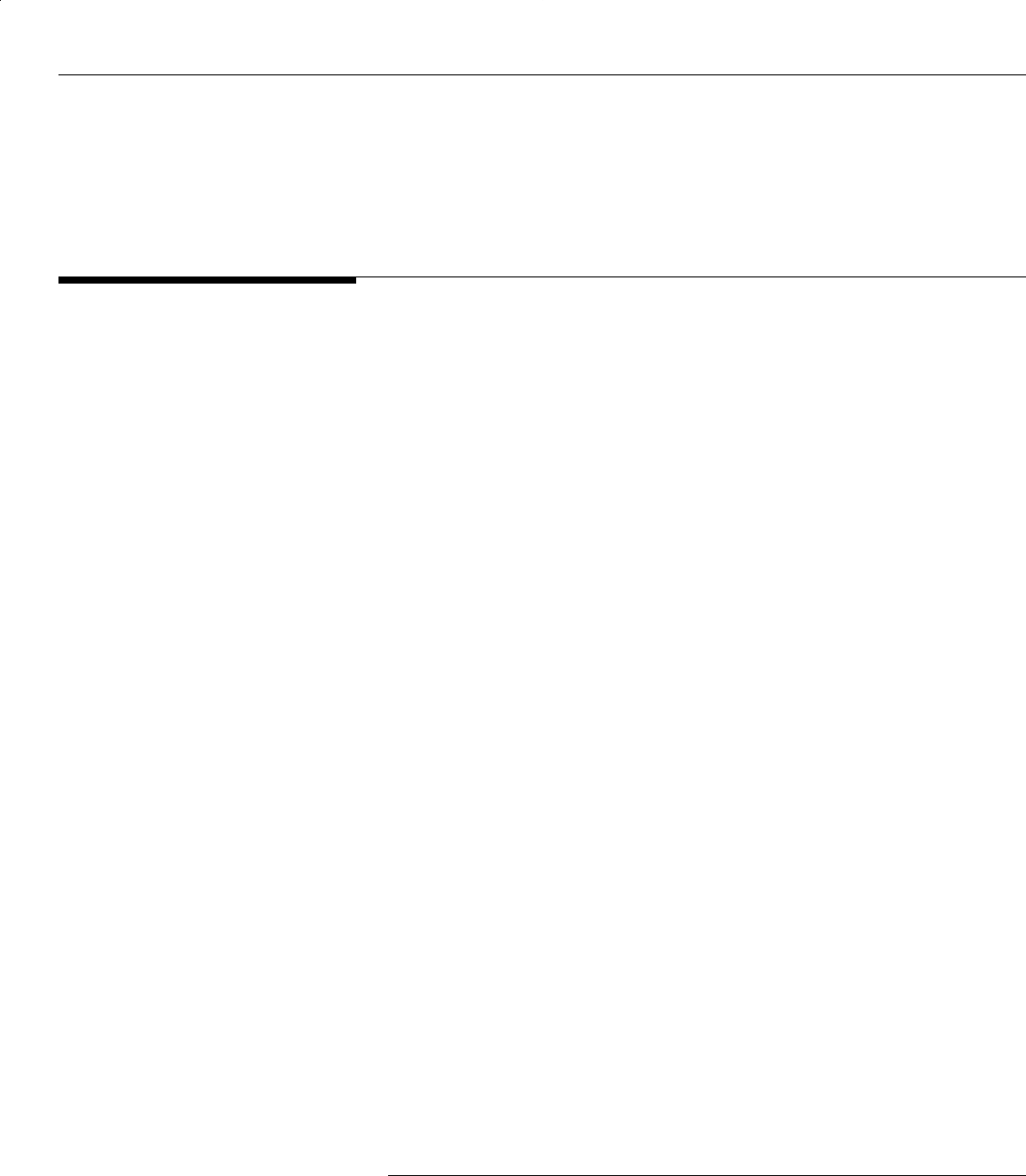

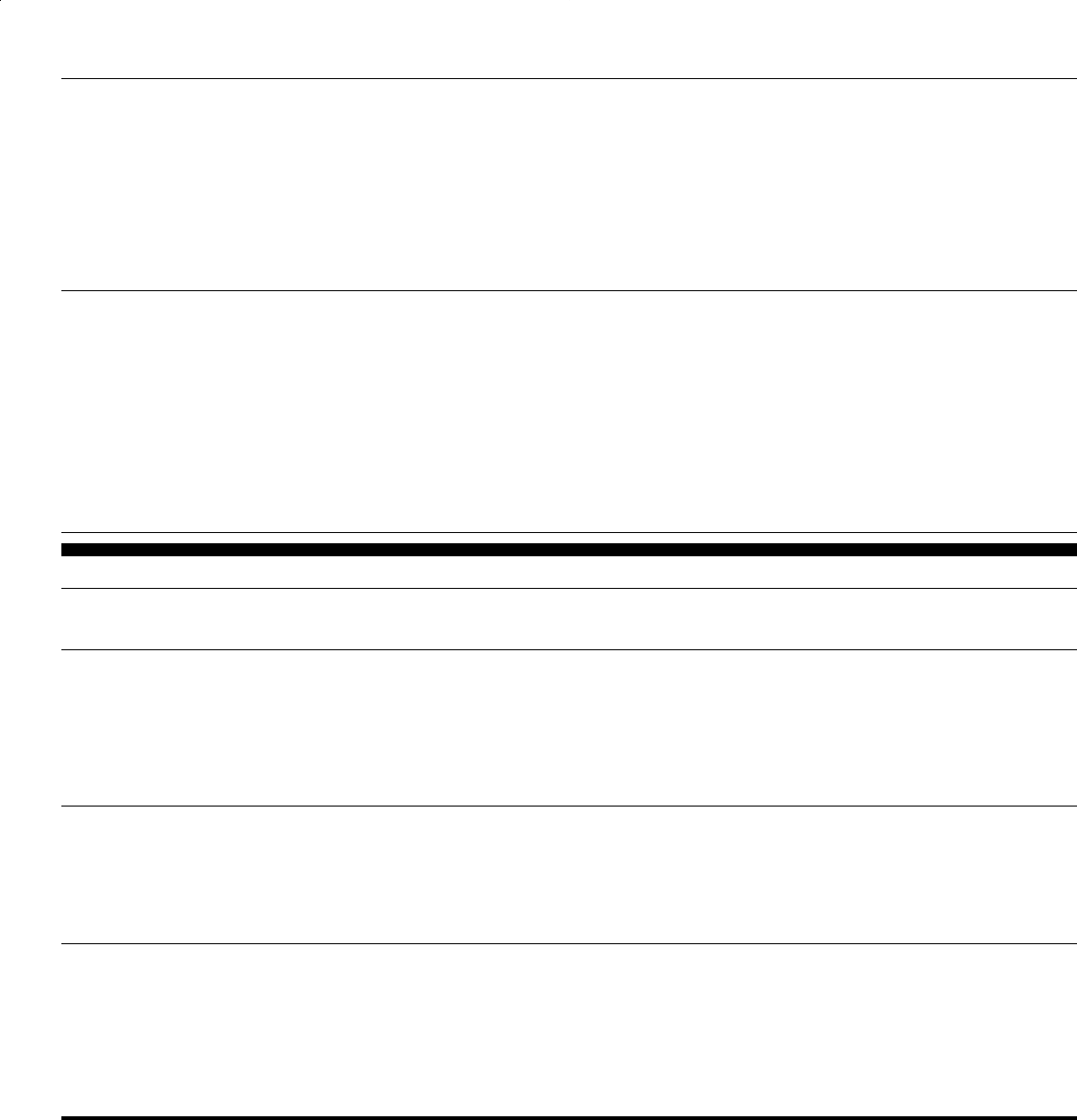

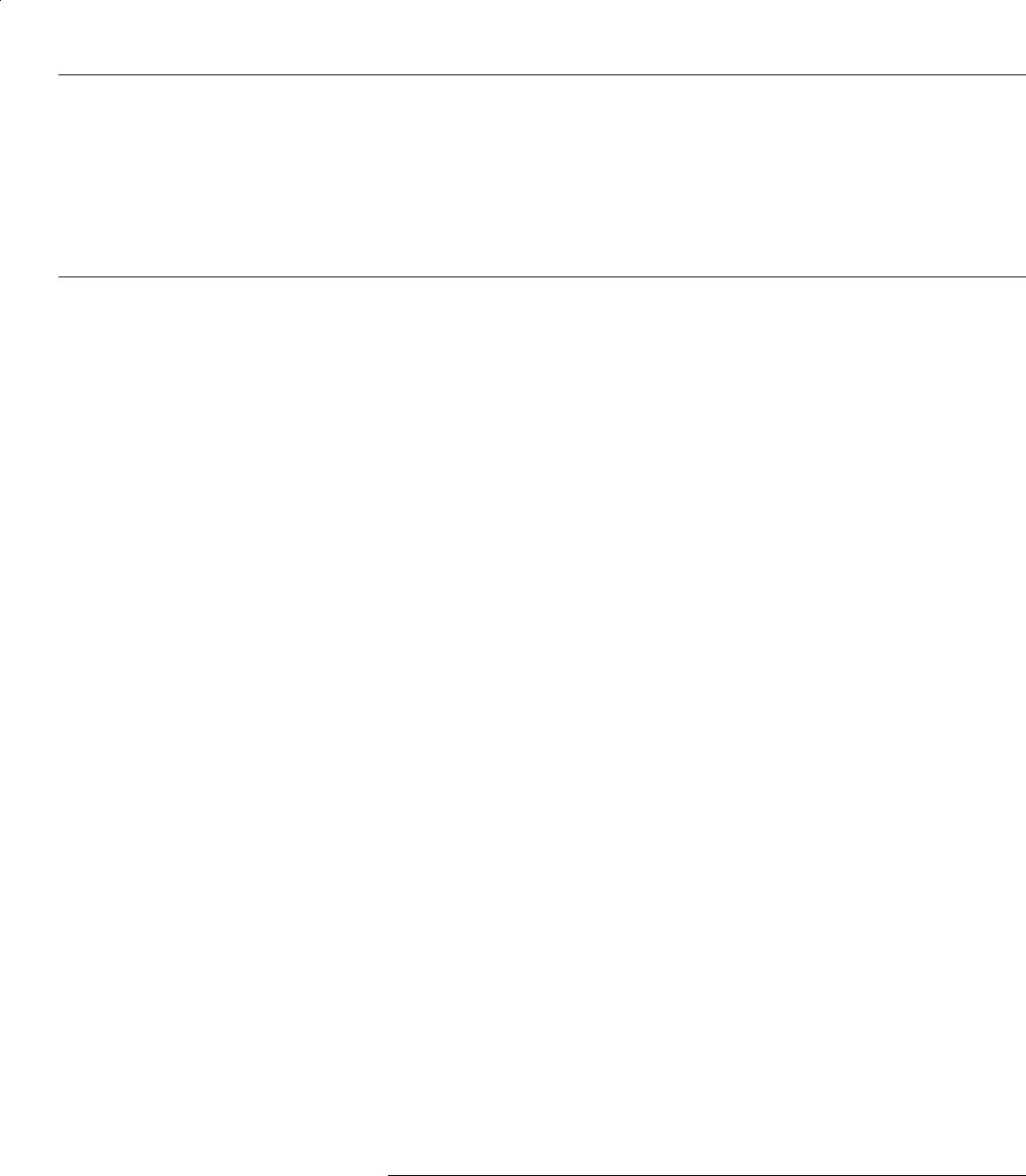

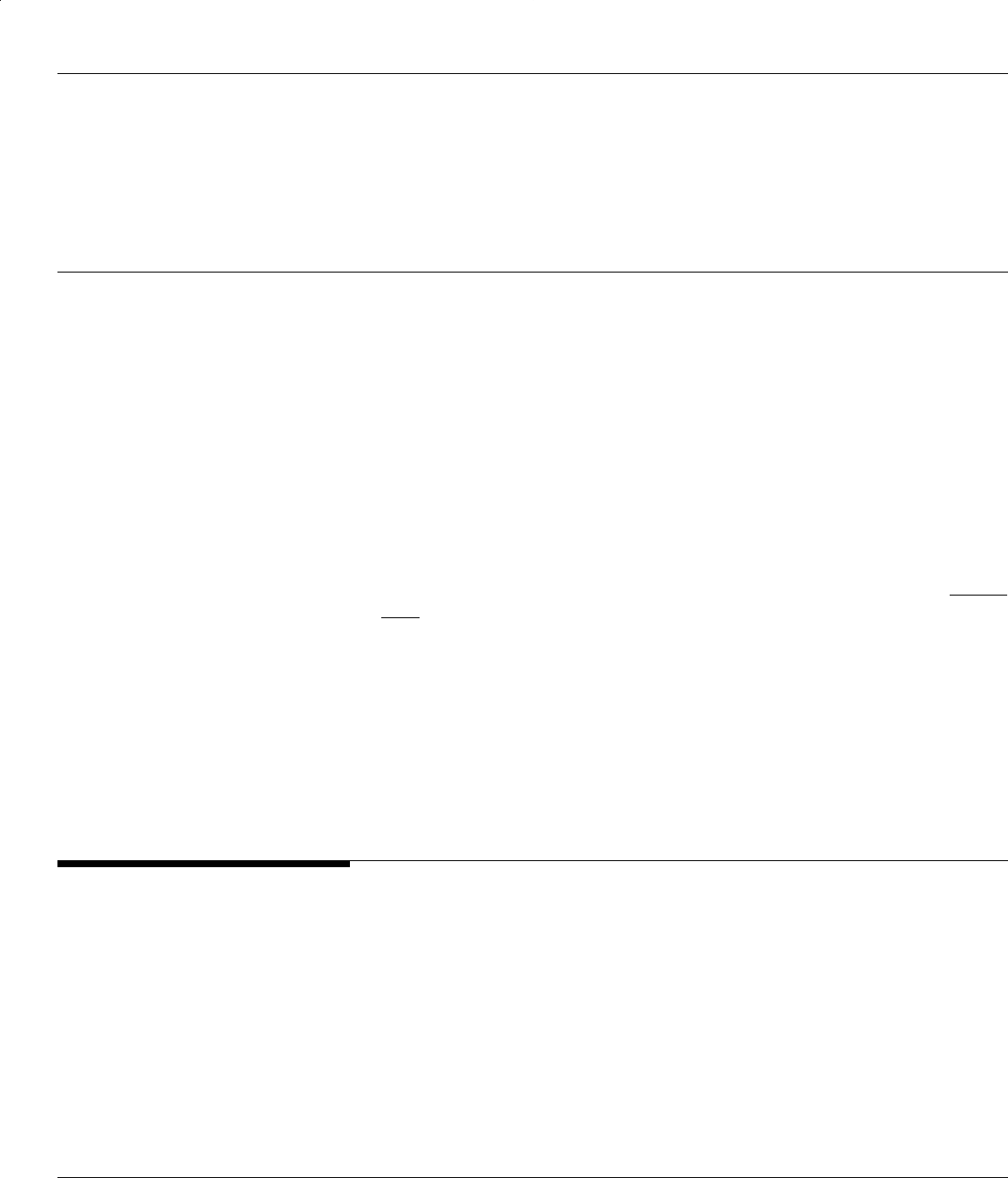

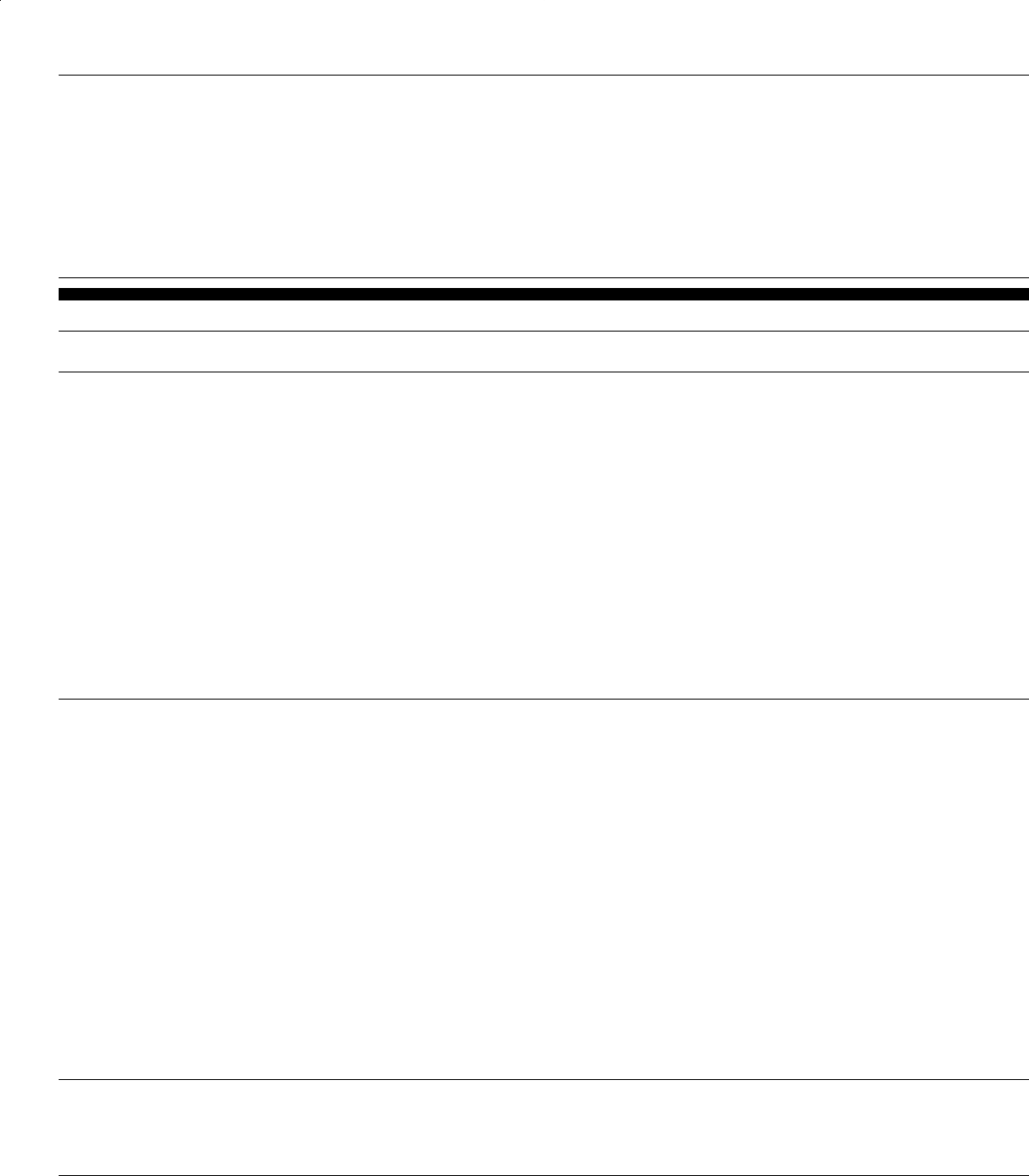

grown as rapidly in the last 15 years. As figure 1 shows, in 1998 one-quarter

of all full-time workers held jobs in the service sector, which makes it the

largest employment sector.

Figure 1: Percentage of Full-Time Wage and Salary Workers in 1983 and 1998 by Industry

Notes: The sampling errors for the estimates in this figure do not exceed plus or minus

0.5 percentage points at the 95% significance level.

Service industries included four types of service occupations from the Current Population Survey

(CPS) industry codes: business and repair, personal, entertainment and recreation, and

professional and related services. For definitions of other industries discussed in this report, see

app. I.

Source: CPS Outgoing Rotations Data for 1983 and 1998.

In addition to growing rapidly, the service sector also has a higher

proportion of exempt workers than other sectors and is responsible for

much of the growth in the exempt population. Not only has the service

sector grown by 11 million full-time workers in the last 15 years, but the

number of exempt workers in the service sector has increased by

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 9

B-283016

3.6 million.

11

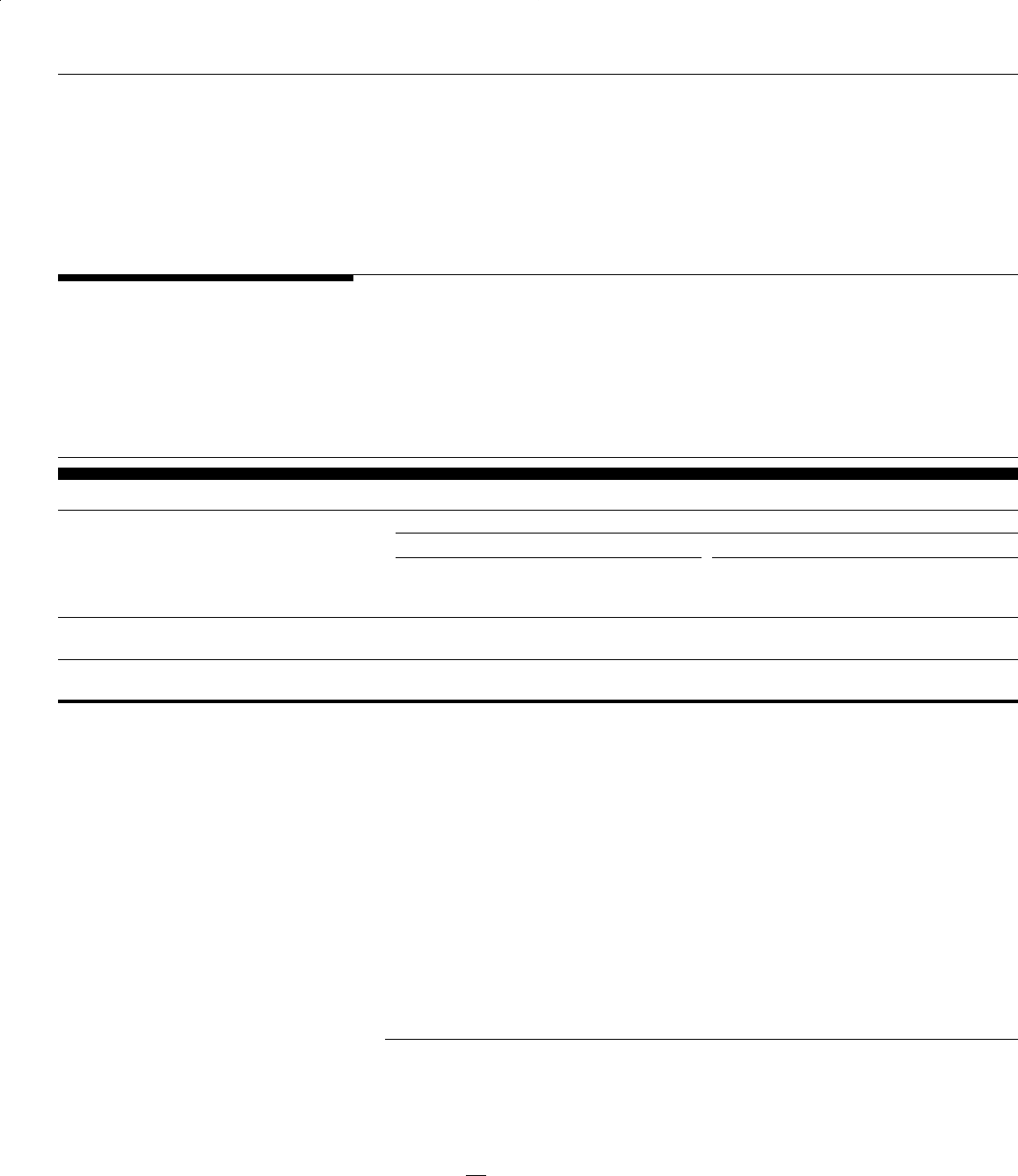

Over the last 15 years, the increase in the number of full-time

workers covered by the white-collar exemptions has been about 8 million.

The increase of 3.6 million exempt workers in the service sector over this

same time represents about 46 percent of the overall growth in exempt

workers. As a result of this rapid growth, 29 percent of all exempt workers

worked in the service sector in 1998—up from 19 percent in 1983 (see

figure 2).

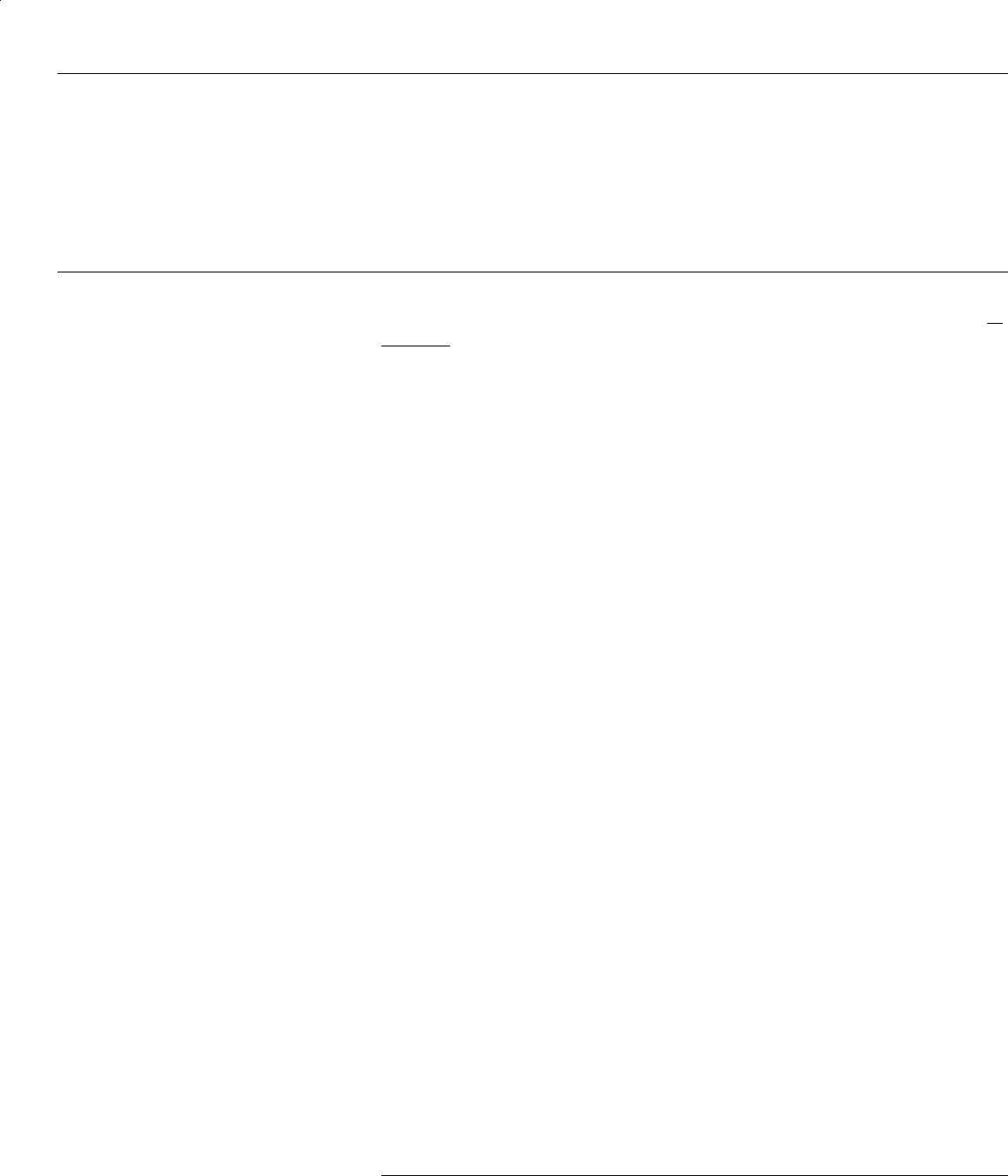

Figure 2: Percentage of Full-Time White-Collar Workers Exempt in 1983 and 1998 by Industry

Notes: The percentage estimates represent the average of the high and low estimates. See app. I

for a discussion of these estimates.

Service industries included four types of service occupations from the Current Population Survey

(CPS) industry codes: business and repair, personal, entertainment and recreation, and

professional and related services. For definitions of other industries discussed in this report, see

app. I.

Source: CPS Outgoing Rotations Data for 1983 and 1998.

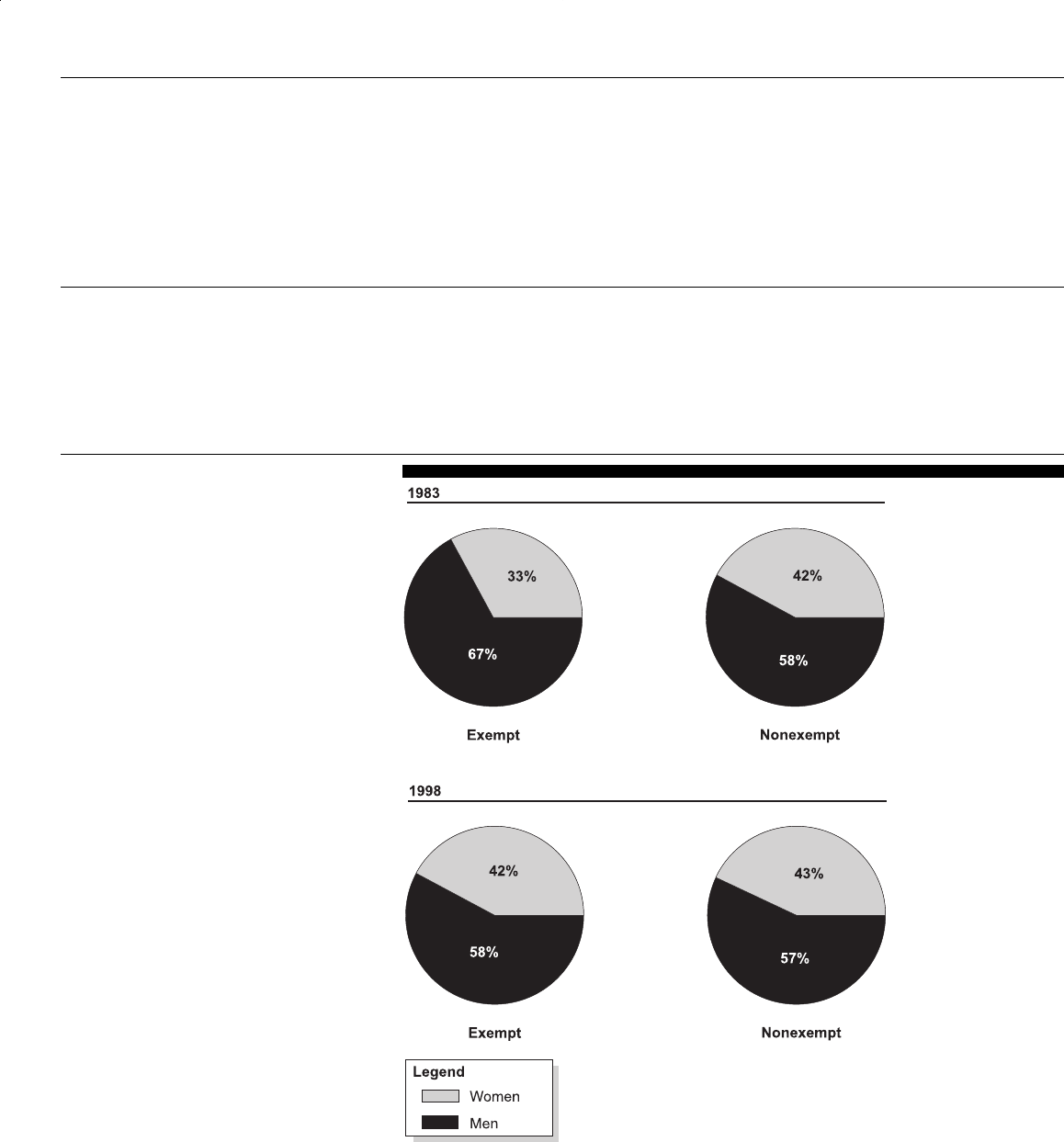

The demographic composition of the exempt population has significantly

changed in the last 15 years. In 1998, 42 percent of exempt workers were

11

This estimate and those that follow represent the average of the high and low estimates. Please see

app. I for a discussion of these estimates.

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 10

B-283016

women, compared to 33 percent in 1983 (see figure 3). On the other hand,

the gender distribution of nonexempt workers has not changed in the last

15 years. About 40 percent of nonexempt workers were women in both

1983 and in 1998. These data indicate that more women than men entered

full-time white-collar positions over this period.

Figure 3: Percentage of Full-Time

White-Collar Exempt and Nonexempt

Workforce in 1983 and 1998 by Gender

Note: The percentage estimates represent the average of the high and low estimates. See app. I

for a discussion of these estimates.

Source: CPS Outgoing Rotations Data for 1983 and 1998.

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 11

B-283016

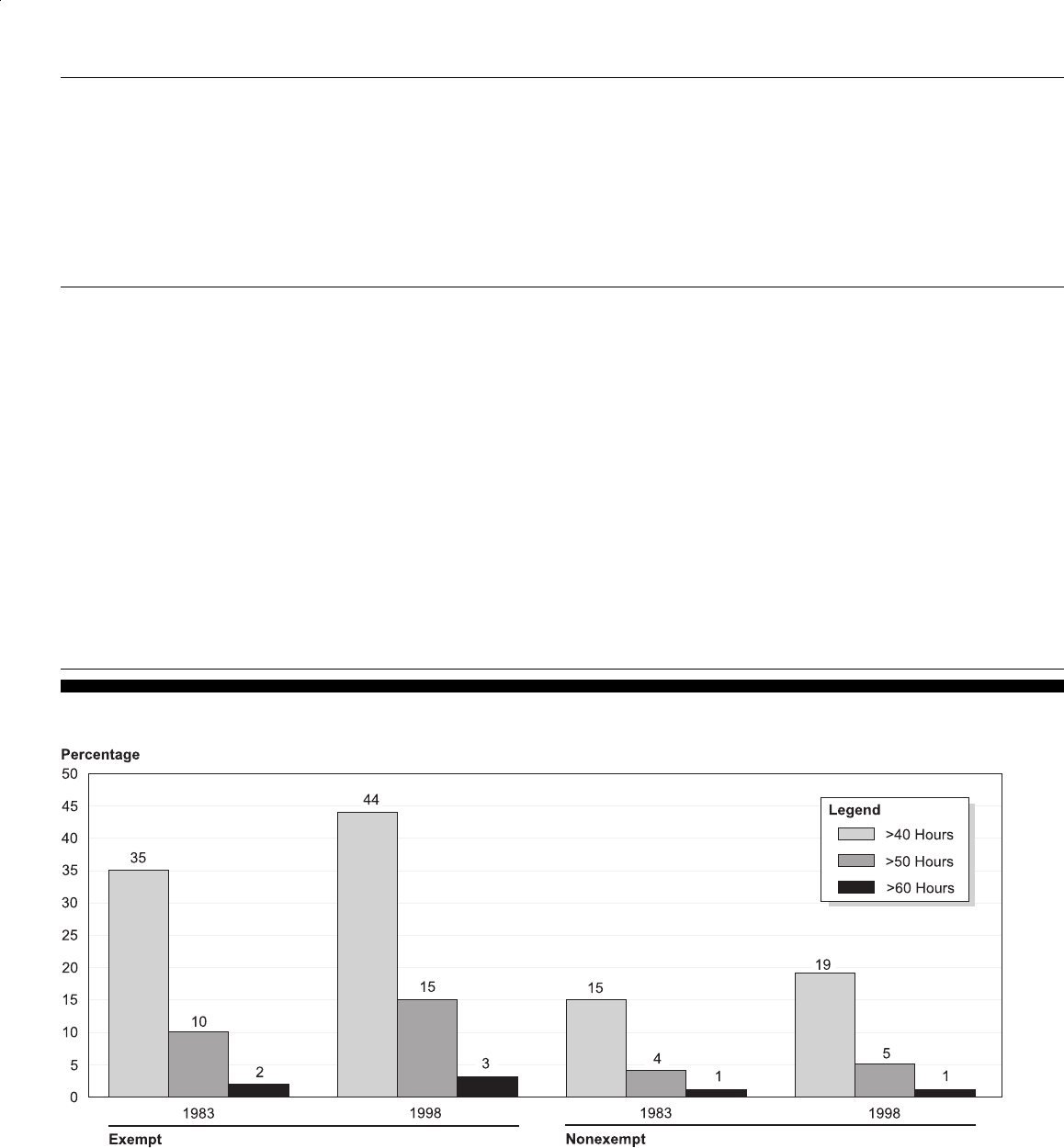

Full-time workers covered by the white-collar exemptions are much more

likely to work overtime—that is, more than 40 hours per week—than

nonexempt workers (see figure 4). As figure 4 shows, in 1998, nearly

half—44 percent—of the 19 to 26 million full-time workers covered by the

exemptions said they worked overtime at their primary job. In 1983, about

one-third—35 percent—of full-time exempt workers worked more than 40

hours per week. In fact, exempt workers were more than twice as likely to

work overtime in both 1983 and 1998 as nonexempt workers. In general,

the amount of overtime hours worked by both exempt and nonexempt

workers was greater in 1998 than in 1983. In this regard, in 1998, about

15 percent of exempt workers worked more than 50 hours per week and

3 percent worked more than 60 hours per week at their main job. This

compares to 10 percent working more than 50 hours per week and

2 percent working more than 60 hours in 1983.

Figure 4: Percentage of Full-Time Exempt and Nonexempt White-Collar Workers Who Worked Overtime in 1983 and 1998

Note: The percentage estimates represent the average of the high and low estimates. See app. I

for a discussion of these estimates.

Source: CPS Outgoing Rotations Data for 1983 and 1998.

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 12

B-283016

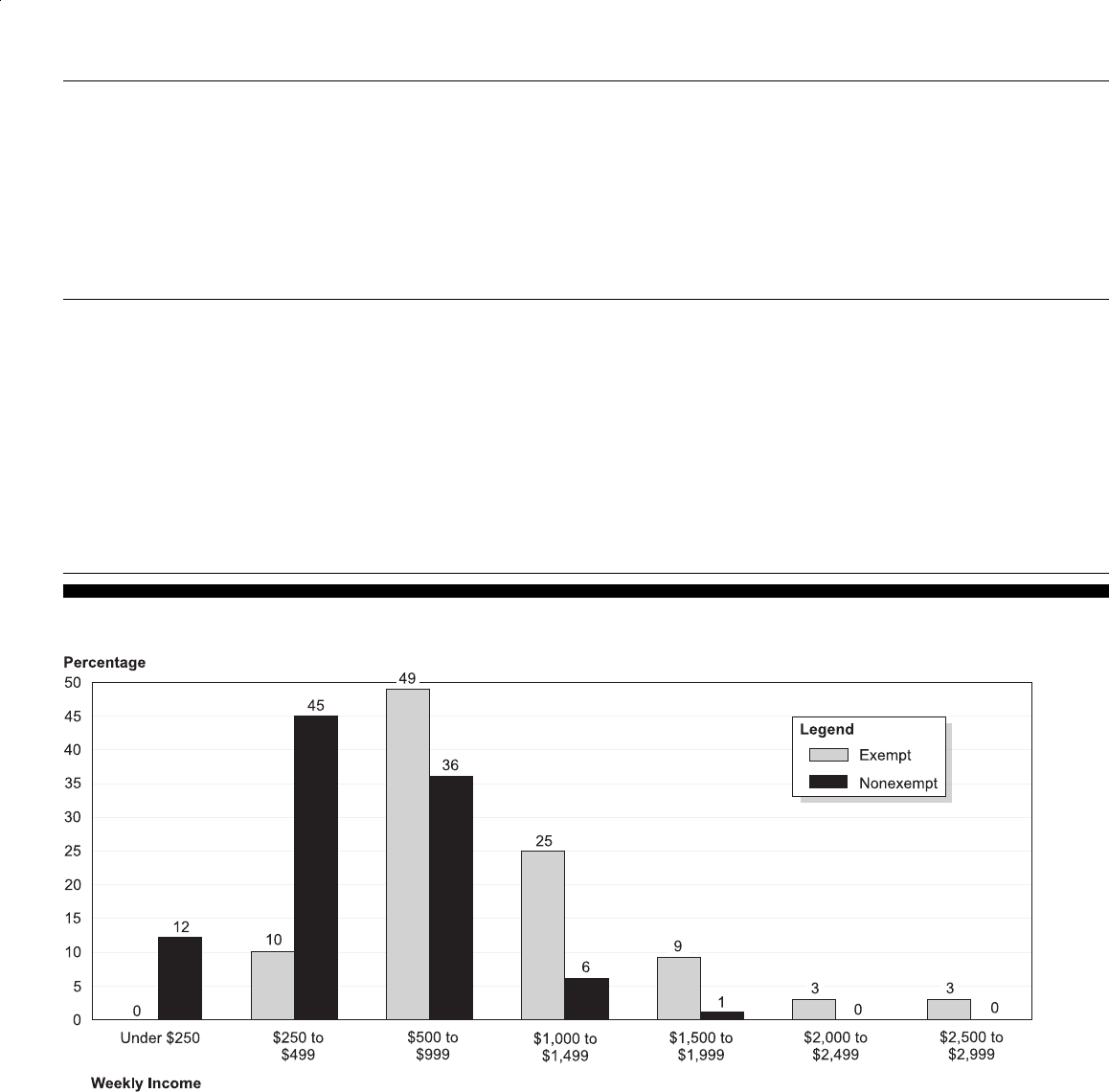

As figures 5 and 6 show, exempt workers earned substantially more than

nonexempt workers in 1998. In figure 5, 40 percent of exempt workers

earned $1,000 or more per week, compared to only 7 percent of

nonexempt workers. Conversely, 57 percent of nonexempt workers

earned less than $500 per week, compared to only 10 percent of exempt

workers.

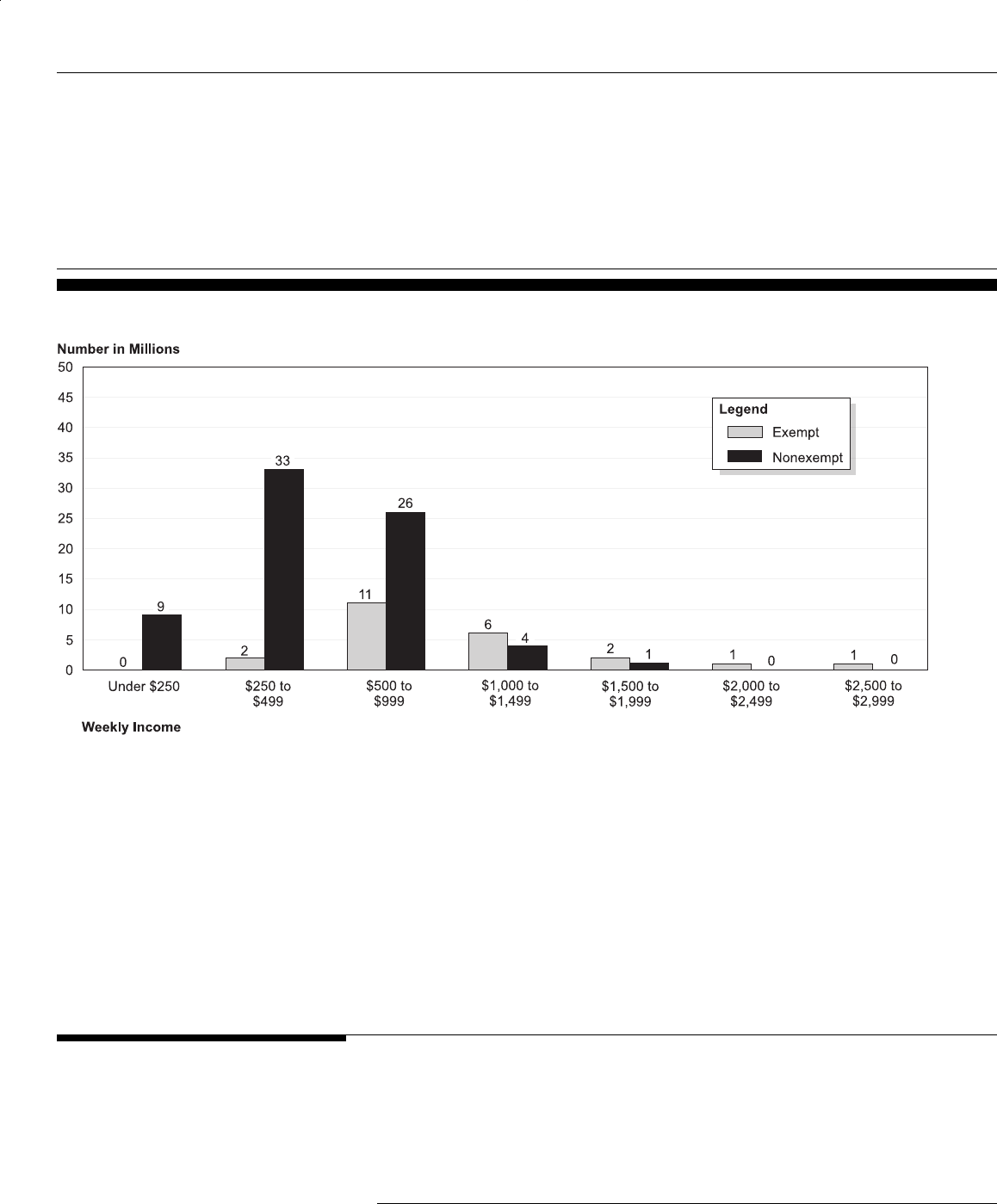

Figure 6 illustrates that there are many fewer exempt workers than

nonexempt workers.

Figure 5: Percentage of Full-Time Exempt and Nonexempt White-Collar Workers in 1998 by Weekly Income

Note: The percentage estimates represent the average of the high and low estimates. See app. I

for a discussion of these estimates. The zero percentages in this table are the result of rounding

and represent a number between 0 and 0.5 percent.

Source: CPS Outgoing Rotations Data for 1998.

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 13

B-283016

Figure 6: Number of Full-Time Exempt and Nonexempt White-Collar Workers in 1998 by Weekly Income (in Millions)

Note: The numerical estimates represent the average of the high and low estimates. See app. I for

a discussion of these estimates. The zeros in this table are the result of rounding to the nearest

million and represent a number between 0 and 500,000 people.

Source: CPS Outgoing Rotations Data for 1998.

In 1998, the average weekly earnings of full-time exempt workers were

nearly twice those of nonexempt workers—$1,018

12

weekly compared to

$526 for nonexempt workers. The difference in earnings between exempt

and nonexempt workers was similar in 1983.

Few Major Changes in

Exemption Laws and

Regulations Since

1954

In the 61 years since the enactment of the FLSA, there have been few major

changes to the statutory and regulatory provisions for the white-collar

exemptions. Between 1938 and 1954,

DOL established its basic set of

regulatory tests—the salary-basis test, the salary-level tests, and the

various duties tests. Although

DOL made a public request for views on

restructuring the regulations in 1985, it has not acted to alter the general

12

The earnings figures reported here are earnings from the respondent’s main job before taxes or other

deductions including earnings from overtime pay, commissions, or tips from that job.

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 14

B-283016

way the regulatory tests work since 1954. Changes after 1954 have

primarily involved adjustments to the salary-test levels and to the tests

applicable to specific types of workers, such as retail workers, state and

local government employees, and computer programmers.

In the 16 years following the enactment of the

FLSA in 1938, DOL established

the regulatory tests used to determine whether an employee should be

classified as an exempt white-collar worker. These tests evolved as

DOL’s

experience with administering the tests grew. For example, the first set of

regulations in 1938 included a single test for executives and

administrators. Two years later, responding to numerous criticisms,

DOL

drafted two separate definitions—one for “executives,” to apply to people

who are bosses, and another for “administrative” employees, to apply to

people who carry out management policies but who do not supervise other

employees.

DOL made its final change to the structure of the basic tests in

1954, when it adjusted the exceptions to the salary-basis requirement.

Since 1954, statutory and regulatory revisions have, in general, either

(1) adjusted the salary levels upward or (2) modified the coverage of the

exemption, extending or reducing coverage for a particular type of

worker. The salary levels were adjusted in 1958, 1963, 1970, and 1975.

DOL

last attempted to increase these levels in 1981; a Presidential order,

however, indefinitely postponed these increases. In 1961, statutory and

regulatory revisions eliminated a separate exemption covering most retail

workers and specifically included these workers under the white-collar

exemptions. Other statutory and regulatory changes expanded coverage of

the exemptions to teachers (1967)

13

and certain higher-wage computer

professionals (1992). A regulatory revision in 1992 limited the effect of the

salary-basis requirement for state and local governments.

All statutory and regulatory revisions on white-collar exemptions are

presented in appendix II. The major changes are summarized in table 3.

13

As pointed out in table 3, public educational institutions were not covered by the FLSA until 1967.

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 15

B-283016

Table 3: Summary of Major Statutory

and Regulatory Revisions to the

White-Collar Exemptions

Year of revision Summary of revision

1938 through 1954 Basic regulatory tests set forth in regulations

1961 Separate retail trade exemption repealed but retail

employees were included, with a limitation, under the

general coverage of the white-collar exemption

1967 FLSA was applied to public educational institutions but

teachers and school administrators were included under

the exemption

1973 The equal pay provision of the FLSA was made

applicable to all those included under the white-collar

exemption

1992 Under certain circumstances, state and local government

workers were excepted from selected aspects of the

salary-basis requirement

Certain computer professionals earning over 6-1/2 times

the minimum wage were exempted from the FLSA, even

though they were paid an hourly wage

Source: GAO analysis of statutory and regulatory provisions.

Employers Believe the

Regulatory Tests Are

Too Complicated and

Outdated for the

Modern Work Place

From our reviews of 166 federal court cases

14

involving litigation on this

subject and 66

DOL compliance cases,

15

as well as our discussions with

employers,

DOL officials, and various legal and economic experts, the

following three issues stood out as being of particular concern to

employers:

• First, the complex requirements of the salary-basis test or the so-called

“no-docking” rule presented possibly the greatest potential liability for

employers and made it difficult to account for employees’ time and

actions.

• Second, the traditional limits of the white-collar exemptions between the

highly paid, very skilled nonexempt technical workers and the exempt

professional and administrative employees have been blurred in the

modern work place.

• Third, the requirement for independent judgment and discretion on the

part of administrative and professional employees was a major area of

contention in

DOL audits involving the white-collar exemptions.

14

We reviewed 5 years of judicial opinions (1994 through 1998) for both federal district court and

federal appellate court cases.

15

We reviewed 66 compliance cases closed in the past 2 years in four DOL field offices.

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 16

B-283016

Employers Cite Perceived

Difficulties of Salary-Basis

Test

The salary-basis test requires that exempt white-collar employees be paid

a set salary each pay period, rather than an hourly wage. The test appears

to rest upon the assumption that employers would pay managerial and

professional employees who are key to their business operations a

guaranteed salary regardless of the number of hours worked. In the

DOL

enforcement program, this test is viewed as an accurate indication of

managerial and professional status. The test, however, effectively limits

the ability of employers to “dock” exempt employees’ pay for such things

as part-day personal absences and disciplinary violations (hence, the

so-called no-docking rule). Employers object to the test because in their

opinion (1) compliance requires exacting adherence to the no-docking

requirements, leaving them vulnerable to private lawsuits by multiple,

well-paid employees; and (2) it limits their ability to hold their exempt

employees accountable for their time and actions.

In general,

DOL regulations specify that employees can be exempt

executives, administrators, and professionals only if they are paid on a

salary basis—that is, employers must pay them a full salary for any week

worked “without regard to the number of days or hours worked.” Although

there are exceptions to this rule,

16

a private employer

17

may not dock an

exempt employee’s pay for absences of less than a full day—for whatever

reason—without violating the salary-basis test. In addition, neither public

nor private employers can dock an exempt employee’s pay for periods of

less than a week to enforce disciplinary rules except for a violation of a

safety rule of major significance. Employers, therefore, must pay exempt

employees a full weekly salary even though the employees may, for

example, take time off during the day for an extended lunch or a visit to

the dentist. Further, employers cannot suspend exempt employees without

pay for less than 1 week for such things as tardiness or unexplained

absenteeism.

In our interviews, employers and their representatives discussed the

complex requirements of the salary-basis test, and their concerns that if

they should not comply with the requirements, they may face lawsuits

brought by multiple (and possibly highly paid) employees for back wages

and other damages. Under the

FLSA, employees may sue their employer

either individually or collectively for up to 2, and in some cases 3, years of

16

Exceptions to the rule include deductions of a day or more for personal reasons other than sickness

and accident, deductions of a day or more for sickness if in accordance with company policy, and

deductions for violation of safety rules of major significance.

17

A 1992 amendment to the regulations allowed state and local governments to dock employees’ pay

for part-day absences under certain circumstances.

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 17

B-283016

back wages plus other damages. In our review of federal court cases, we

found that the salary-basis test has been the central focus of cases brought

by employees against their employers. Our review of 166 federal cases

involving the white-collar exemptions litigated in the past 5 years showed

that about 50 percent involved employee suits alleging that employers

improperly claimed exemptions for employees who did not meet the

salary-basis test.

For the most part, the salary-basis cases involved groups of supervisory or

professional employees collectively suing their employers. However, the

large majority of cases were initiated by groups of managerial public

employees (such as police and fire chiefs, senior corrections officers)

against state and local governments,

18

most often because the government

could suspend or had suspended the pay of exempt employees as a

penalty for disciplinary infractions. Overall, over 70 percent of the

salary-basis cases were collective actions, and about 70 percent were

lawsuits against state and local governments.

A 1997 Supreme Court case, Auer v. Robbins

, reduced employers’ potential

for liability from these lawsuits.

19

In this case, a large group of senior

police officers sued a city government because its disciplinary suspensions

appeared to apply to exempt officers even though the city had only

suspended one police sergeant. The court ruled in favor of the city, and

effectively limited employers’ liability for improper pay docking to cases

where there is an “actual practice” or a “significant likelihood” of such

action. Prior to this decision, some federal cases had ruled that an

employer did not meet the salary-basis test if there were only a possibility

that the employer might improperly dock an exempt employee’s pay. The

result of this ruling is that fewer cases have resulted in liability for

employers—our review of 42 federal cases following Auer

showed that 30

were decided in favor of the employers. However, the full effect of the

Auer

ruling has yet to be determined.

Our discussions with employers and review of other federal cases showed

a variety of circumstances in which employers were uncertain about the

18

In a recent decision, Alden v. Maine, 119 S.Ct. 2240 (1990), the Supreme Court ruled that state

employees cannot sue a state in state courts for overtime wages under the FLSA if the state has not

waived its sovereign immunity. A previous Supreme Court decision, Seminole Tribe of Fla. v. Florida,

517 U.S. 44 (1996), precluded such suits in federal courts.

19

519 U.S. 452.

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 18

B-283016

limits of the test. Some examples

20

of questions concerning these

circumstances include the following:

• What constitutes an “actual practice” of pay docking? When does one

instance connote an actual practice?

• When can employers correct instances of improper pay docking and not

incur liability?

• What happens when an employee has no accrued leave? Can an employer

deduct from accrued compensatory time?

• The Family and Medical Leave Act requires employers to give employees

unpaid leave for serious medical conditions; if such leave is taken in

partial-day increments, does it violate the salary-basis test?

• Under what circumstances can employers pay hourly overtime to exempt

workers and maintain time sheets or set work hours?

• Can an employee be disciplined for failure to complete a work shift?

• An employer cannot suspend an exempt employee for less than a week; if

the suspension is for more than a week, must the employer suspend the

employee only in weekly increments?

In Auer

, the Supreme Court expressly deferred to the Secretary of Labor

as the expert on regulatory interpretation of the salary-basis test.

According to legal experts we talked to, clear guidance to employers from

DOL on the technical requirements of the test may resolve some

uncertainties. However, they indicated that it can be difficult for the public

to locate published legal advice from

DOL. As one solution, they suggested

that

DOL make its “opinion letters”—legal guidance it routinely provides to

individual employers—more widely available to the general public, for

example, by putting them on the Internet.

However, even where the requirements of the salary-basis test were

relatively clear, employers argued that the effects on their operations

created anomalies. In the retail industry, for example, employers cannot

dock an exempt employee’s pay to recoup losses from cash shortages or

employee theft. If they do so, the employee is considered nonexempt and

entitled to overtime wages. Employers complained that this rule unduly

limits their ability to recover losses where responsibility clearly rests with

one employee, such as when an employee delivering cash receipts to a

bank loses the cash or an employee uses a corporate credit card for

personal items.

20

In commenting on this report, DOL stated that it believes some of the legal issues raised by

employers have been authoritatively addressed in either the case law or the law itself. Our review of

the case law indicates that legal conclusions on issues related to the salary-basis test can vary

depending upon the factual circumstances of individual cases.

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 19

B-283016

Officials from three large local governments

21

told us that the salary-basis

test made it difficult to penalize employees with systematic disciplinary

steps. All three local governments are heavily unionized and to satisfy the

union contracts they must use “progressive discipline.” This means that

before harsh disciplinary actions—such as long-term suspensions or

termination—can be used to discipline an employee, less severe

disciplinary measures—such as part-day suspensions without pay—must

be taken to alert the employee to performance problems. However, the

officials contend that the salary-basis test prevented them from taking

such lesser measures.

DOL officials told us that they believe that payment on a salary basis

remains one of the best indicators of managerial and professional status.

This belief is longstanding. As a 1940

DOL report explained:

. . . The term “executive” implies a certain prestige, status, and importance. Employees who

qualify under the definition are denied the protection of the act. It must be assumed that

they enjoy compensatory privileges and this presumption will clearly fail if they are not

paid a salary substantially higher than the wages guaranteed as a mere minimum under

section 6 of the act. In no other way can there be assurance that section 13 (a) (1) will not

invite evasion of section 6 and section 7 for large numbers of workers to whom the

wage-and-hour provisions should apply. Indeed, if an employer states that a particular

employee is of sufficient importance to his firm to be classified as an “executive” employee

and thereby exempt from the protection of the act, the best single test of the employer’s

good faith in attributing importance to the employee’s services is the amount he pays for

them. The reasonableness and soundness of this conclusion is sustained by the record.

A 1949 DOL report rejected proposals to eliminate the salary-basis test,

commenting that “[C]ompensation on a salary basis appears to have been

almost universally recognized as the only method of payment consistent

with the status of the ‘bona fide’ executive . . . [and] is one of the

recognized attributes of administrative and professional employment.”

These principles were again reaffirmed in the report and

recommendations of a 1958 hearing report on proposed revisions to the

regulations.

Compliance investigators in

DOL’s Wage and Hour Division said that the

salary-basis test is a key enforcement test. Investigators told us that the

21

Because it is clear that local governments (and other employers) violate the salary-basis test when

they discipline their management officials by suspensions without pay, all three local governments we

talked to have made large groups of their employees nonexempt rather than give up their disciplinary

systems. One now pays its senior police officials overtime, another has limited its exempt workers to

those paid over $73,000 per year, and the third has made nearly all union workers nonexempt

(90 percent of its employees are unionized).

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 20

B-283016

first review they routinely undertake involves determining whether the

exempt employees are paid on a salary basis. However, as one investigator

explained to us, testing for compliance can be difficult because most often

exempt employees have worked in excess of 40 hours and have been paid

for at least 40 hours, making it hard to prove that employers have made

improper deductions to the salaries of exempt workers. Although we

found that the salary-basis test was not the central issue in most

compliance cases we reviewed, it was critical to some cases. In one case,

for example, a gas service station owner paid managers and assistant

managers a salary of $400 per week and required them to work 60 hours

per week. Although the owner claimed the employees to be exempt

executives, the investigator successfully challenged their executive status

because the owner reduced their pay if they worked less than 60 hours per

week.

Employers Say Some

Production Workers Are

Equivalent to White-Collar

Employees

Nonsupervisory employees may be exempt from the FLSA if they can be

classified as either administrative or professional employees. However, the

administrative exemption is limited to those employees who perform

nonmanual (or nonproduction) work “directly related to the management

policies or general business operations” using independent judgment and

discretion, and the professional exemption is generally limited to

occupations requiring advanced academic degrees.

22

Thus, as interpreted

for the past 60 years, these exemptions do not apply to many technical

workers—nonsupervisory line workers who work to produce the

employer’s goods and who do not have the requisite academic degree for a

recognized profession in which they are employed.

In our discussions with employers and state and local government

representatives, both groups argued that the traditional limits of the

white-collar exemptions are outdated in the modern work place. They

believed that certain highly skilled, well-paid line workers should be

treated as exempt workers because they have the knowledge equivalent to

an exempt professional. Officials from manufacturing employers pointed

to new technology used in factory work places, which they said required

advanced technical skills but required far less traditional “manual” labor.

Moreover, they told us that while these workers may have to follow

precise written guidelines to perform their work, prescribed procedures

were key to modern quality control. State and local representatives

pointed to job classifications within their organizations which involved

22

There are, however, exceptions for certain specific occupations such as computer programming,

based on a 1990 congressional enactment, and work of an artistic nature.

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 21

B-283016

line work but which required the knowledge and experience of a civil

service professional.

To illustrate the point, one company official described the job of

technicians who maintain unmanned factories around the country. In her

company, one technician, relying upon standardized instruments, monitors

each automated factory. The official compared the nonexempt line jobs of

these well-paid (about $70,000 per year) technicians with those of her

company’s engineers. Both groups held similar jobs and earned

comparable pay, but because the engineers had professional degrees and

the technicians did not, only the engineers could be classified as exempt

professional employees.

In general, employers pointed to the differences between exempt and

nonexempt employee status as creating difficulties in managing the

workforce, particularly in what they referred to as crossover positions like

the technicians described above. According to the employers, nonexempt

employees have less flexibility in work shifts—any work over 40 hours

must be paid at overtime rates, even if the employee is planning on

working less than 40 hours in the next work-week. Further, employers

claim that workers look on exempt status as prestigious, allowing greater

possibility of management promotion. In addition, employers also believed

that adherence to strict written guidelines—one major distinction between

exempt and nonexempt workers—is necessary in a modern, efficient work

place.

In recent years, the distinctions between production and nonproduction

workers, and between professional and technical production workers,

have been increasingly blurred. The federal court cases and

DOL

compliance cases we reviewed provided illustrations of recent distinctions

made between exempt and nonexempt nonsupervisory workers. These

cases included the following:

• A large publishing firm employed about 50 production editors, each of

whom managed the final publication processing of the company’s books.

One of these production editors sued the company, claiming that she was

improperly classified as an exempt employee. A federal appellate court

ruled that, although her job involved production work, she was an exempt

employee. It found that her work was a major assignment of the company

and, therefore, that it was directly related to the management policies or

business operations of the company.

23

23

Shaw v. Prentice Hall Computer Publishing, Inc., 151 F.3d 640 (7

th

Cir. 1998).

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 22

B-283016

• An insurance company employed automobile damage appraisers to

determine the amount to be paid on auto insurance claims. A federal

district court found the appraisers to be nonexempt production workers

because they did not do work related to the management policies or

business operations of the firm. Rather than administratively running the

business, they carried out the daily affairs of the company.

24

• A title insurance company used escrow closers to conduct final property

settlements. A federal district court held that these were nonexempt

employees who were carrying out the day-to-day operations of the

company

25

and that it was irrelevant that they were not part of the

company’s production department.

• One southern state’s Department of Agriculture employed dairy inspectors

and food safety inspectors. The dairy inspectors had academic training

and experience in the specific area of dairy or animal sciences, while the

food safety inspectors had more generalized academic training in

biological sciences.

DOL compliance review determined that only the dairy

inspectors met the educational requirement of the professional exemption.

The Requirement for

Independent Judgment and

Discretion Is Difficult to

Apply

To be classified as either an exempt administrative or professional

employee, each employee must exercise independent judgment and

discretion in carrying out his or her job duties. In general, the requirement

for exercising independent judgment and discretion means that employees

have the freedom to make choices about matters of significance to their

employers, without immediate supervision or detailed guidelines. Factors

which are taken into account include (1) the amount of supervision,

(2) the amount of written guidelines, and (3) whether the work involves

routine matters. For example, a newly hired accountant may be given

work that is closely supervised, involving rote work with set procedures.

In that case, the accountant would be nonexempt, even though he or she

may have full professional certification.

Our discussions with employers and

DOL investigators indicated that this

aspect of the regulations is particularly difficult to apply for both the

employers and the investigators. Employers complained that the standards

for the independent judgment requirement were confusing and applied in

an inconsistent manner by

DOL. Thus, employers were unsure of how to

properly classify administrative personnel. According to

DOL investigators,

determinations about independent judgment and discretion can be the

most difficult part of a compliance review. To assess this requirement, an

24

Reich v. American International Adjustment Co., Inc., 902 F. Supp. 321 (D. Conn. 1994).

25

Reich v. Chicago Title Insurance Co., 853 F. Supp. 1325 (D. Kan. 1994).

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 23

B-283016

investigator must review both the general duties of the position and the

specific duties of the employee. Further, the determination may hinge

upon how an individual employee views his or her own duties. For

instance, one administrative assistant may look at his job as answering

telephone calls and following orders, while another person in the same

position might describe the job as involving the independence to establish

office procedures and respond to incoming client inquiries.

The compliance cases we reviewed included a number of instances where

the standard for independent judgment and discretion was key to

determining the employee’s status. Situations where this question arose

included the following:

• A trucking company employed dispatchers to organize and schedule truck

routes. Two of the dispatchers negotiated with other companies to obtain

contracts for truck loads, as well as scheduling truck routes. The

DOL

compliance investigator allowed the administrative exemption for the two

senior dispatchers, but not for the other dispatchers.

• A firm provided library services to professional firms. Firm officials

claimed that certain librarians were exempt as either administrative or

professional employees. The

DOL investigator disagreed, finding the

librarians were nonexempt because their work—filing and updating

loose-leaf volumes—was “routine and not dependent on a professional

degree.”

• An architectural firm hired professional architects and engineers. The firm

classified its employees according to experience, but considered them all

exempt. The

DOL investigator found that architects and engineers at the

entry level were nonexempt, because they did not exercise discretion and

independent judgment in their jobs.

In our review, we noted certain cases in which an employer conducted its

own self-audit and used this to negotiate a final settlement with

DOL. One

large accounting firm agreed to conduct a self-audit of all of its entry-level

tax reporting accountants, and

DOL agreed to not question the application

of the professional exemptions to second- and third-year accountants. In

another example,

DOL investigators found certain job titles at a commercial

bank that appeared to involve nonexempt work. To settle the compliance

questions, the bank hired a law firm to conduct an audit of individual

employee classifications. The lawyers examined the bank’s

FLSA

classifications and recommended that changes be made. With the approval

of

DOL, the bank accepted the reclassifications suggested by the audit and

agreed to pay the necessary back wages.

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 24

B-283016

Employees Say That

Inflation and

Oversimplification

Have Undermined

Exemption Limits

Employee representatives and other experts were particularly concerned

that the use of the exemptions be limited, maintaining the 40-hour

work-week standard for as many employees as possible. To do this, they

were of the opinion that the regulatory tests should provide the type of

protection originally intended. In this regard, the following two issues

seemed particularly important to employees:

• The salary-test levels that underpin the regulatory framework have been

unchanged since 1975. Because of inflation, the current salary-test levels

are now near the minimum-wage level, rendering the application of certain

regulatory tests to the current workforce virtually meaningless.

• The duties test that determines who can be classified as an exempt

executive has been increasingly simplified by judicial opinions. When

combined with the low salary-test levels, employees believe that few

protections remain for lower-income supervisors.

Inflation Has Effectively

Eliminated Important

Aspects of the Regulatory

Tests

In determining whether an employee is exempt from the FLSA as an

executive, administrator, or professional, the first consideration is the

employee’s salary. Since 1949, employees have been divided into three

groups according to their weekly earnings. As described earlier in table 2,

the standards vary depending on whether an employee is to be classified

as an executive, administrator, or professional. For the executive

exemption, the three groups currently are as follows:

• Employees earning less than $155 per week are automatically nonexempt

(or subject to the

FLSA requirements).

• Employees making at least $155 but less than $250 per week are

nonexempt unless their duties meet the rigorous standards of the so-called

long duties test. The long duties test for executives requires that

employees’ duties include such things as the authority to hire or fire other

employees and the ability to exercise discretion; most significantly,

though, it sets percentage limitations on the amount of nonmanagerial

work an exempt employee can perform in a work-week. Specifically,

employees qualify as exempt employees only if no more than 20 percent

(or less than 40 percent for retail and service employees) of their jobs

involve nonmanagerial or nonprofessional work.

• Employees earning at least $250 per week are exempt as long as their

duties meet the less strict standards of the so-called short duties test, an

abbreviated version of the long duties test. The short duties test does not

specify percentage limitations on the amount of nonmanagerial work an

exempt employee can perform. For executives, the test is limited to

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 25

B-283016

requiring that employees supervise two or more workers and that their

primary duty is managerial.

The practical differences between the long and short duties tests are

significant. To illustrate, consider a cook who supervises a crew of other

workers. If the cook’s salary was $200 per week, and he was thus subject

to the long duties test, he would be nonexempt (and entitled to overtime

wages) if he spent more than 40 percent of his time on nonmanagerial

tasks—work such as cooking food or cleaning the kitchen. If, however, the

cook’s salary was $250 per week, the cook would be an exempt executive

as long as his primary duty was management and included the customary

and regular direction of at least two other employees, even though he may

spend a lot of time cooking food or cleaning the kitchen.

The salary levels used to determine into which of the three salary

categories an employee falls have not been changed since 1975. During

that time period, salaries in the nation have risen considerably. As a result,

the salary levels used by

DOL for this purpose, which in 1975 were

considered fairly high, are now below the level of the federal minimum

wage in the instances of the base salary levels. Even the higher level, $250

per week, is equivalent to an hourly wage that is only $1.10 per hour higher

than the current minimum federal hourly wage of $5.15 for a 40-hour

work-week. For the salary levels used in this determination to represent

the same level of purchasing power now as they did in 1975, they would

need to be considerably higher than their current levels. For example, the

highest of levels, $250 per week, would have to be $757 per week, for an

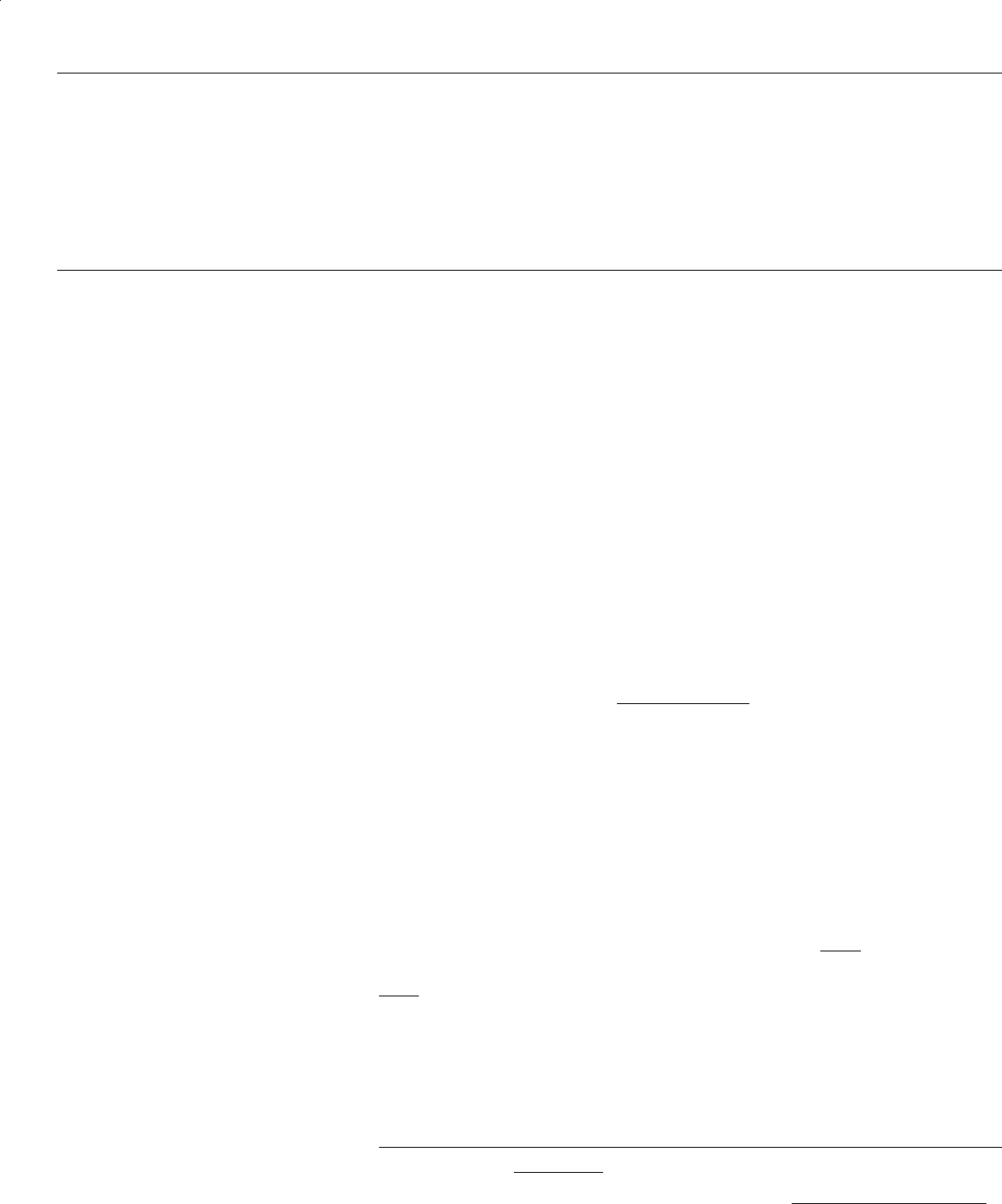

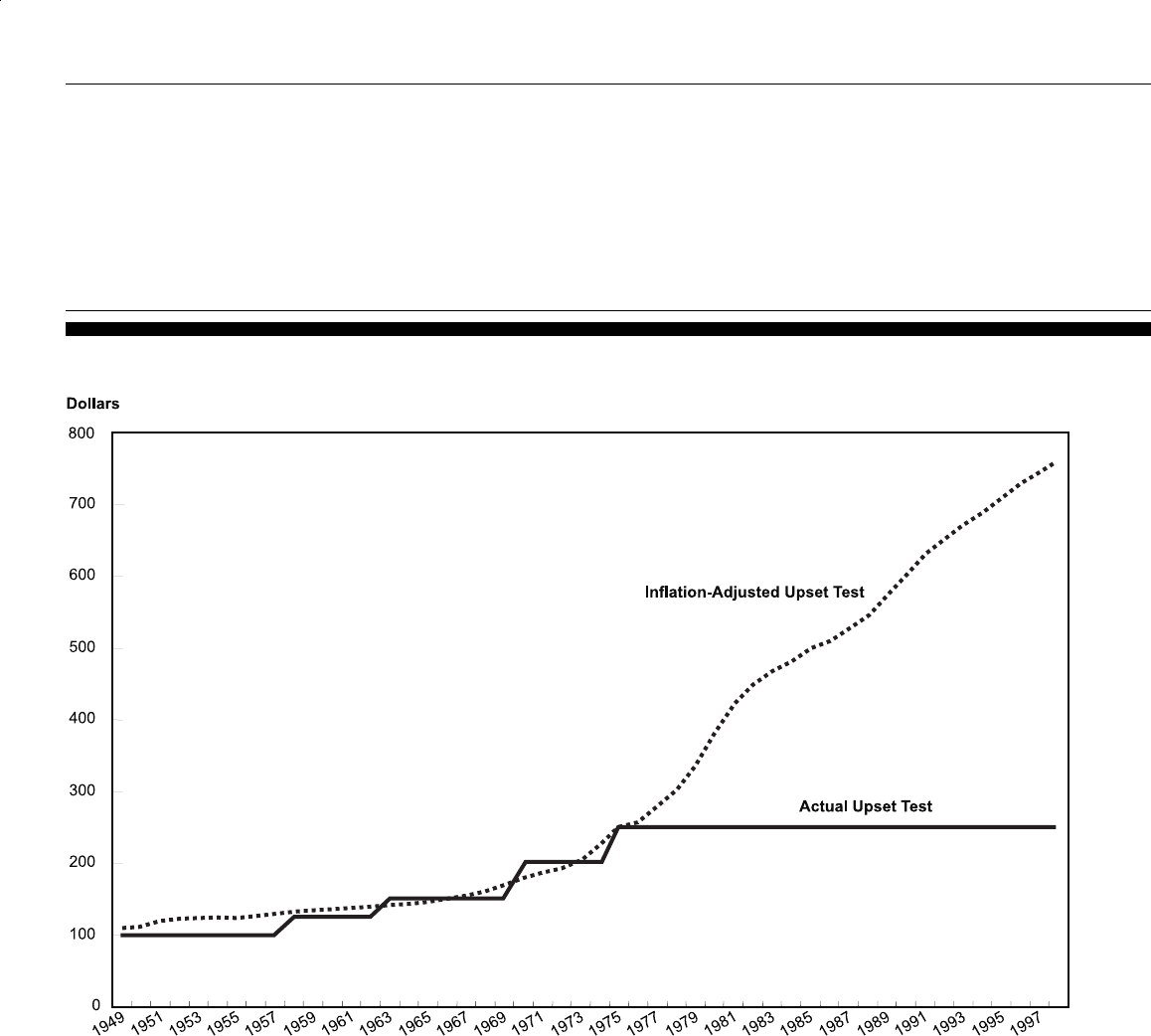

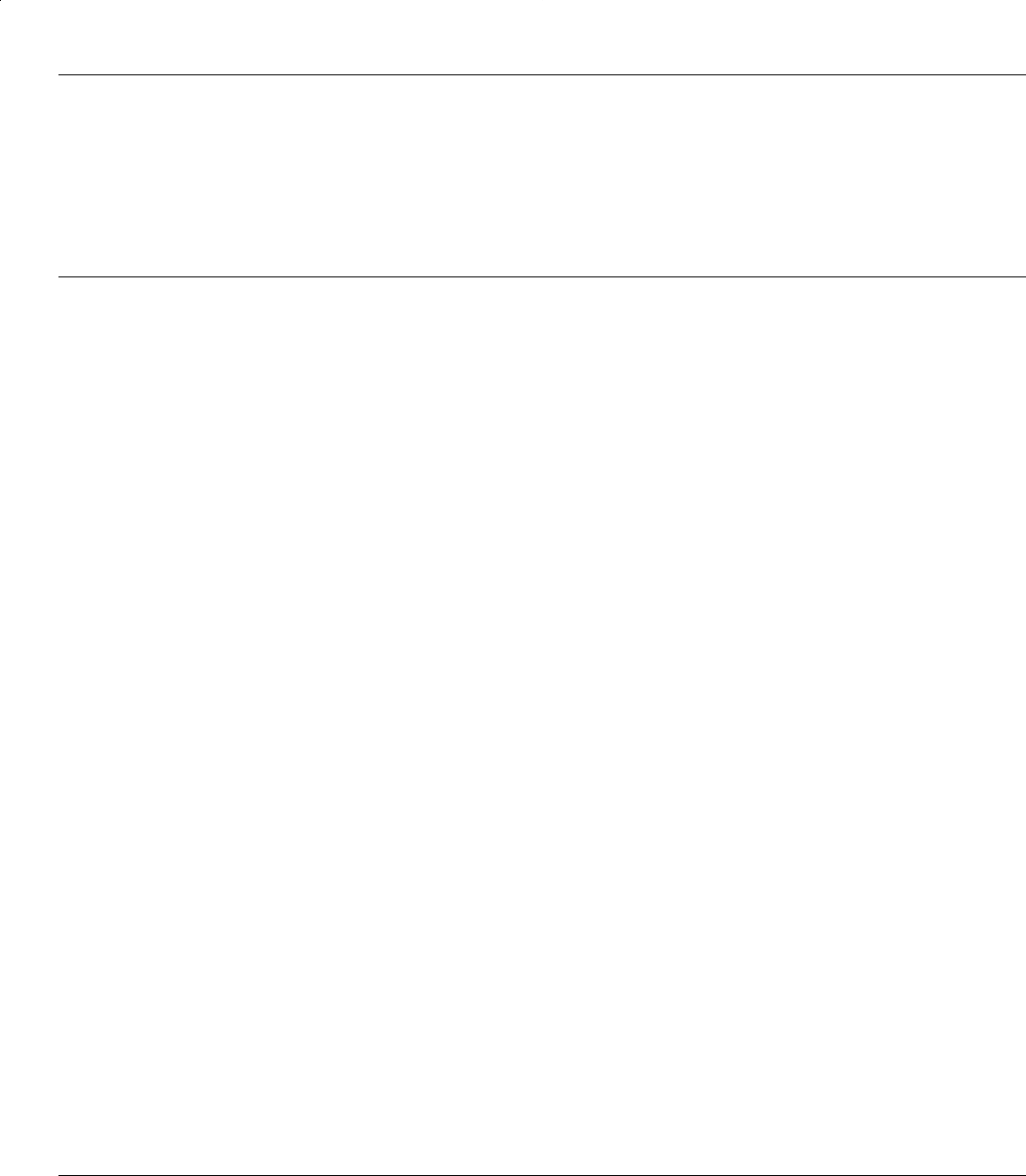

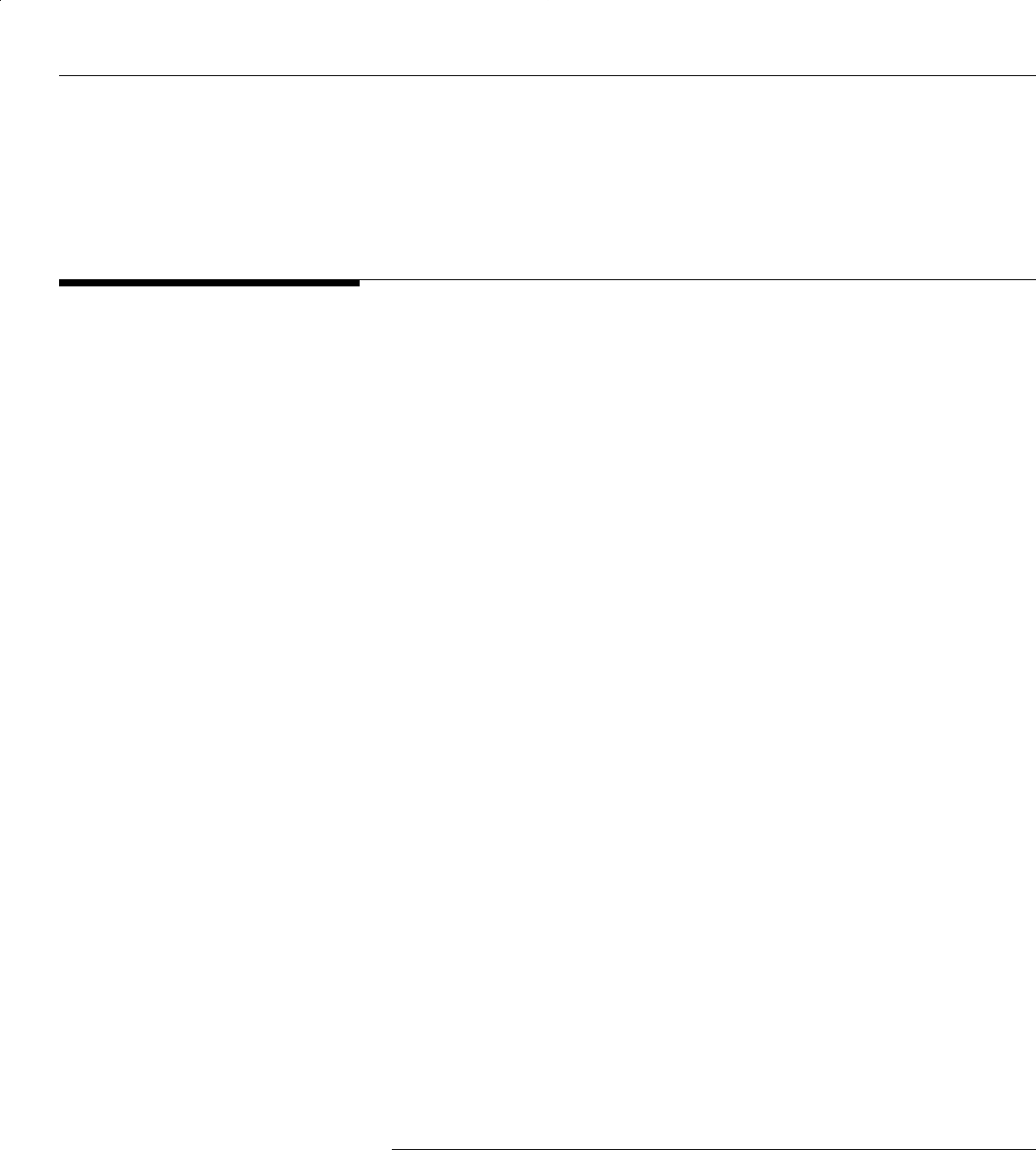

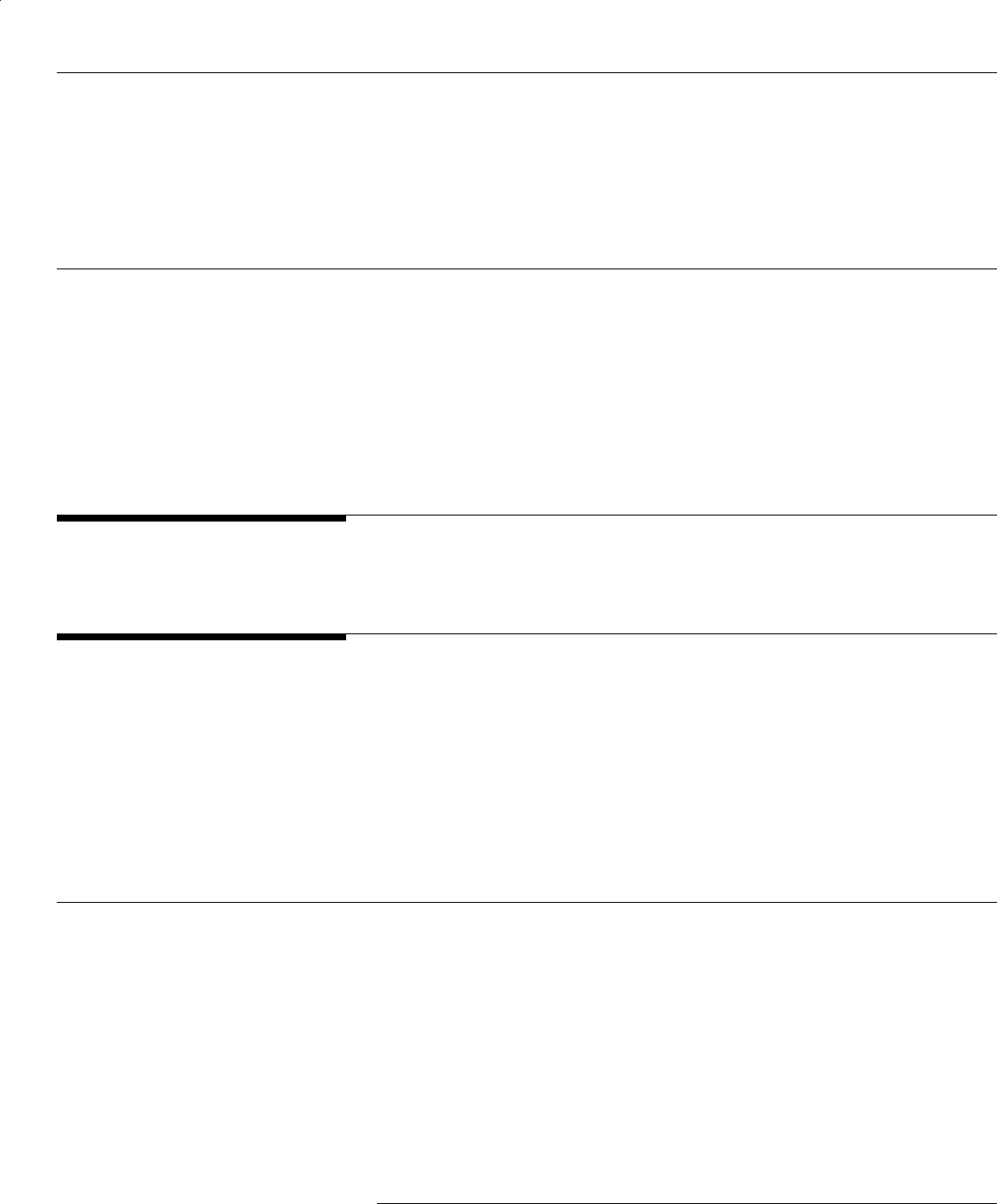

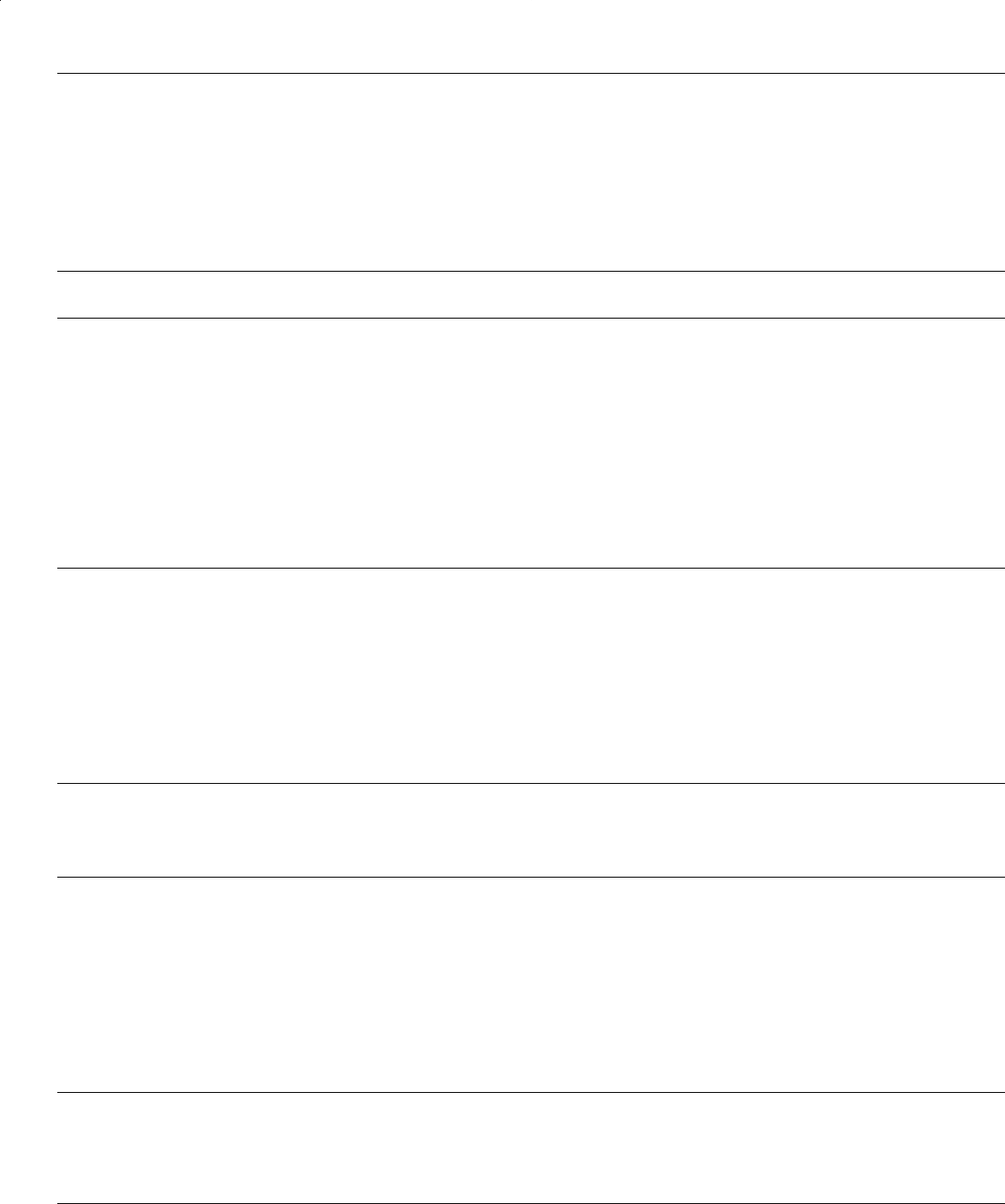

annual salary of about $39,400. In figure 7, we examine the highest salary

level over the 49-year period between 1949 and 1998, and we compare the

actual level included in the regulations with the level necessary to keep

pace with inflation.

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 26

B-283016

Figure 7: Actual and Inflation-Adjusted Highest Salary Test, or Upset Test, for Weekly Income, 1949-1998

Note: Upset test numbers are adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index for all Urban

Consumers (CPI-U), with 1975 as the base year.

Source: Data for the actual upset test are from 29 C.F.R. chap. V, part 541; inflation-adjusted

upset test calculated by GAO.

To see the effect of inflation on the application of the regulatory tests,

consider again the example of the supervisory cook. Today, the cook

would be automatically nonexempt only if his salary was less than $8,060

per year—the equivalent of $3.88 per hour, $1.27 less than the current

federal minimum wage. The strict long duties test would apply only if he

made less than $13,000 (equivalent to an hourly rate not much higher than

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 27

B-283016

the minimum wage for a 40-hour work-week). And, as long as he made

$13,000, he would be presumed to be an executive if his primary duty was

management—for example, if he can hire and fire workers.

However, if the cook’s salary was adjusted to include the inflation

occurring between 1975 and 1998, the application of the regulatory tests

would be very different. Using salary figures adjusted for inflation, the

cook would be automatically nonexempt as long as he earned less than

$24,400. If he earned between about $24,400 and $39,400, he would be

exempt only if his work met the long duties test. And, if he earned more

than $39,400, he would be an exempt executive if his primary duty were

management.

Because of inflation, the percentage of full-time workers who potentially

fell into each of the three salary level categories was far different in 1975

than in 1998

26

—specifically,

• In 1975, about 30 percent of the full-time workforce would have been

automatically nonexempt workers; in 1998, only 1 percent of the full-time

workforce were automatically nonexempt.

27

• In 1975, about 30 percent of the full-time workforce would have been

nonexempt unless they met the percentage limitation on performing

nonexempt work; in 1998, the long duties test would apply to only

8 percent of the full-time workforce.

• In 1975, about 40 percent of the full-time workers could have qualified as

exempt workers with the application of the short duties test; in 1998,

91 percent of the workers were under the short duties test.

Employees Say That Duties

Test Offers Little

Protection for

Lower-Income Supervisors

During the past 20 years, it has become increasingly easy to classify a

supervisory employee as an exempt executive. If an employee makes over

$250 per week ($13,000 per year), the employee may be an exempt

executive if he or she meets two criteria. First, the employee must

customarily and regularly direct the work of two or more employees; and

second, the employee’s primary duty must involve management. Unlike

the administrative and professional exemptions, there is no express

26

The data we used for these estimates include full-time wage workers as well as full-time salaried

workers age 16 years and over. The data were provided by BLS and are unpublished tabulations from

the CPS. The data for 1998 are annual averages while the data for 1975 are for the month of May, when

annual averages were not available. Self-employed workers are excluded.

27

These percentages are approximate; the CPS data provide the percentage of workers who earn under

$150 per week, rather than under $155 per week, the base salary for exempt executive and

administrative employees.

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 28

B-283016

requirement for independent judgment and discretion. However, the

regulations specify that, “as a rule of thumb,” an employee who spends

more than 50 percent of his or her time on management tasks would have

management as a primary duty.

Two federal court decisions in 1982 clarified the test for determining

whether an employee earning over $250 per week has management as a

primary duty. The cases, involving litigation between

DOL and the Burger

King Corporation,

28

applied the executive exemption to assistant managers

at the fast-food restaurants. First, one decision held that the duties of

Burger King assistant managers were primarily managerial, even though

the company provided them detailed instructions on how they were to

perform their work. Second, both courts found that the 50-percent “rule of

thumb” limitation on nonmanagerial work was only one factor to consider

when determining employees’ primary duty, and that their managerial

duties could be carried out at the same time they were performing manual

work. Thus, assistant managers could be exempt executives even if they

spent most of the day cooking hamburgers—as long as they were in charge

of the restaurants during their shifts.

While employers appreciate the simplicity and the clarity of the executive

duties test, union representatives complained that the judicial rulings

following the Burger King

decisions have oversimplified the executive test.

Under the regulations, as currently interpreted, almost any employee who

is assigned to supervise two or more employees in a particular

“department” of the company can be classified as an exempt employee.

According to the union officials, employers have adjusted their work

places to include many new levels of supervision in order to create exempt

executive positions. Thus, where a grocery store originally had one or two

store managers, it now has many different departments—the meat

department, the produce department, and others—headed by exempt

executives.

Federal case law in the 5-year period from 1994 through 1998 included

hardly any instances in which a court overturned an employer’s

classification of a lower-income supervisor as an exempt executive. In the

32 cases we identified as relating to the executive exemption duties test,

about one-third (12 cases) involved employees whose salaries were $500

per week (or $26,000 per year) or less. Of these 12 cases, only 1 resulted in

28

Donovan v. Burger King Corp., 672 F.2d 221 (1

st

Cir. 1982), and Donovan v. Burger King Corp., 675

F.2d 516 (2d Cir. 1982).

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 29

B-283016

a favorable ruling for the employee. These cases included a wide range of

employees, such as:

• an aquatics director of a community swimming pool paid $376 per week,

• a produce department manager of a grocery store paid $450 per week,

• a dietary manager of a nursing home paid $341 per week, and

• a loss-prevention manager of a department store paid $423 per week.

All of these employees claimed that their jobs consisted primarily of

nonmanagerial work—for example, life guarding, stocking shelves, and

cooking. Despite evidence of large proportions of nonmanagerial work,

the courts found all but one employee to be exempt executives.

Discussions with

DOL investigators and attorneys suggested that the Burger

King decisions and the low salary-test levels have had a major effect on

their investigation of cases involving exempt executives. Since the

decisions, their policy manual has been revised to require that

investigators consider percentage limitations as only one factor when

assessing the employee’s primary duty. One attorney noted that in recent

years little litigation had been initiated by

DOL over the executive status of

supervisory employees. He indicated that, although there may be

situations in which the exempt executive classification of an employee

supervising two or more workers could be challenged, those situations are

very limited.

Conflicting Interests

of Employers and

Employees Make

Resolution of

Concerns Difficult

Legal and economic experts have proposed various ways to deal with the

concerns raised by employers and employees, ranging from tinkering with

particular provisions of the regulations to a major overhaul of the

FLSA.

However, proposals to change the present law or regulations all affect the

regulatory balance between the desires of employers and those of

employees, and there are competing interests that must be carefully

weighed before any changes can be made. For a number of years,

DOL has

been reluctant to alter the existing tests in view of these competing

interests. To illustrate some of these considerations, we discuss four

proposals that have been made by experts to revise the current

regulations, and summarize the general views of employers and employees

on each.

Eliminate the Salary-Basis

Test

From the employer’s point of view, the salary-basis test presents complex

regulatory requirements—for example, the limitations on the use of pay

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 30

B-283016

suspensions to sanction employees’ actions—that have nothing to do with

managerial or professional status but that can be the source of potential

legal liability for unwary employers. However, if the test were eliminated,

the exemption could be applied to both hourly-wage and salaried workers

and only the other two tests—the salary levels and the duties test—would

remain as indicators of managerial and professional status.

DOL contends

that salary remains the general method of compensation for key

managerial and professional employees. From the standpoint of

employees, the salary-basis test is a key enforcement tool to protect

workers from employers who do not comply with the law because it is an

objective measure of managerial and professional status. For employees, it

is particularly important today because the salary-test levels are so low,

and without the salary-basis test,

DOL would be left only with the

difficult-to-apply duties test as the single test of employer compliance.

In commenting on this report,

DOL further explained the rationale for the

salary tests. According to

DOL, the salary tests have been an integral part of

the definitions for the exemptions since 1940. It believes that the statutory

terms “executive, administrative, or professional” imply a certain prestige,

status, and importance, and an employee’s salary serves as one indicator

of his or her status in management or the recognized professions. It is an

index that distinguishes the bona fide executive from the working squad

leader, or distinguishes the clerk or technician from one who performs

true administrative or professional duties.

DOL said that salary remains a

good indicator of the degree of importance attached to a particular

employee’s job, which provides a practical guide, particularly in borderline

cases, for distinguishing bona fide executive, administrative, and

professional employees from those who were not intended by the

Congress to come within the categories of this exemption. In its years of

experience in administering the regulations,

DOL said it has found no

satisfactory substitute for the salary test. The arguments that the salary

test is not needed or that it does not help draw the proper line between

exempt and nonexempt employees have been offered before, including as

part of the hearings and deliberations over amending the regulations in

1940, 1949, and 1958. As then, the

DOL sees no new or more valid reasons

that have been offered for eliminating the salary test from the regulations

than were considered as part of the previous hearings on this question.

Raise the Salary-Test

Levels

If the salary-test levels were raised, the regulatory structure could

incorporate the effects of inflation and function as originally envisioned.

With a higher salary test, both the long and short duties tests would be

GAO/HEHS-99-164 FSLA and White-Collar ExemptionsPage 31

B-283016

applied once again to segments of potentially exempt workers. Nearly

everyone we talked to—employers, employees, and experts—agreed that

the current salary-test levels are too low and should be increased to

higher, more reasonable levels. However, they disagreed sharply on

whether the duties tests should remain the same after the salary-test levels

were raised.

Employers, particularly retail employers, were opposed to reviving the

long duties test and, with it, the percentage limitation on the amount of

nonmanagerial work that an exempt employee would be allowed to do.

Retail employers argued that the percentage limitations are outdated in